Spoke 19: The Biblewheel and The 19th Century

(Go back to main Menu)

New York the 19th Century Ephesus

The Greek word for shrine used in Acts 19 is naos, which is also translated into temple. The two big events which occurred in the late 19th century New York is the beginning of the building of the Statue of Liberty and the founding of the Shriners secret society. Acts 19 mentions the building of shrines to Diana. The gospel preached by the apostle Paul was a hindrance to the craft.

The Shriners logo has the Arabic sword as well as the crescent moon and star. The crescent moon is a representation of the goddess Diana, called the moon-goddess, as well as representing Allah the moon-god in Islam. The Shriners' intention and direction was to establish ties with the Muslim nations. They also created the Black Nation of Islam in America.

Turkey is known to have the crescent moon and star on it's flag, and the city of Ephesus who once had the temple to the goddess Diana is now in Turkey. Turkey also has a city by the name of Batman, which may be related to the Science Fiction character by the same name. Bob Kane (Robert Kahn) the creator of Batman was a Shriner Mason.

As the Ephesians were crying out for 2 hours, "Great is Diana of the Ephesians", Muslims in protest cry out, "Great is Allah". As Acts 19 mentioned that Diana was the image which fell down from Jupiter, the Ka'aba's Black Stone is believed to have fallen down from heaven as well.

(Go back to main Menu)

New York the 19th Century Ephesus

The Greek word for shrine used in Acts 19 is naos, which is also translated into temple. The two big events which occurred in the late 19th century New York is the beginning of the building of the Statue of Liberty and the founding of the Shriners secret society. Acts 19 mentions the building of shrines to Diana. The gospel preached by the apostle Paul was a hindrance to the craft.

The Shriners logo has the Arabic sword as well as the crescent moon and star. The crescent moon is a representation of the goddess Diana, called the moon-goddess, as well as representing Allah the moon-god in Islam. The Shriners' intention and direction was to establish ties with the Muslim nations. They also created the Black Nation of Islam in America.

Turkey is known to have the crescent moon and star on it's flag, and the city of Ephesus who once had the temple to the goddess Diana is now in Turkey. Turkey also has a city by the name of Batman, which may be related to the Science Fiction character by the same name. Bob Kane (Robert Kahn) the creator of Batman was a Shriner Mason.

As the Ephesians were crying out for 2 hours, "Great is Diana of the Ephesians", Muslims in protest cry out, "Great is Allah". As Acts 19 mentioned that Diana was the image which fell down from Jupiter, the Ka'aba's Black Stone is believed to have fallen down from heaven as well.

Shriners

| Part of a series on |

| Freemasonry |

|---|

|

Shriners International, also commonly known as The Shriners or formerly known as the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine (AAONMS, anagram for A MASON), is a society established in 1870 and is headquartered in Tampa, Florida.[1]

Shriners International describes itself as a fraternity based on fun, fellowship, and the Masonic principles of brotherly love, relief, and truth. There are approximately 350,000 members from 196 temples (chapters) in the U.S., Canada, Brazil, Bolivia, Mexico, the Republic of Panama, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Europe, and Australia. The organization is best known for the Shriners Hospitals for Children that it administers, and the red fezzes that members wear.

The organization was previously known as "Shriners North America". The name was changed in 2010 across North America, Central America, South America, Europe, and Southeast Asia.[2]

Contents

History[edit]

In 1870 there were several thousand Freemasons in Manhattan, many of whom lunched at the Knickerbocker Cottage at a special table on the second floor. There, the idea of a new fraternity for Masons, stressing fun and fellowship, was discussed. Walter M. Fleming, M.D., and William J. Florence took the idea seriously enough to act upon it.

Florence, a world-renowned actor, while on tour in Marseille, was invited to a party given by an Arab diplomat. The entertainment was something in the nature of an elaborately staged musical comedy. At its conclusion, the guests became members of a secret society. Florence took copious notes and drawings at his initial viewing and on two other occasions, once in Algiers and once in Cairo. When he returned to New York in 1870, he showed his material to Fleming.[3]

Fleming created the ritual, emblem and costumes. Florence and Fleming were initiated August 13, 1870, and they initiated 11 other men on June 16, 1871.[4]

The group adopted a Middle Eastern theme and soon established Temples (though the term Temple has now generally been replaced by Shrine Auditorium or Shrine Center). The first Temple established was Mecca Temple (now known as Mecca Shriners), established at the New York City Masonic Hall on September 26, 1872. Fleming was the first Potentate.[5]

In 1875, there were only 43 Shriners in the organization. In an effort to encourage membership, at the June 6, 1876 meeting of Mecca Temple, the Imperial Grand Council of the Ancient Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine for North America was created. Fleming was elected the first Imperial Potentate. After some other reworking, by 1878 there were 425 members in 13 temples in eight states, and by 1888, there were 7,210 members in 48 temples in the United States and Canada. By the Imperial Session held in Washington, D.C. in 1900, there were 55,000 members and 82 Temples.[6]

By 1938 there were about 340,000 members in the United States. That year Life published photographs of its rites for the first time. It described the Shriners as "among secret lodges the No. 1 in prestige, wealth and show", and stated that "[i]n the typical city, especially in the Middle West, the Shriners will include most of the prominent citizens."[7]

Shriners often participate in local parades, sometimes as rather elaborate units: miniature vehicles in themes (all sports cars; all miniature 18-wheeler trucks; all fire engines, and so on), an "Oriental Band" dressed in cartoonish versions of Middle Eastern dress; pipe bands, drummers, motorcycle units, Drum and Bugle Corps, and even traditional brass bands.

Membership[edit]

Until 2000, before being eligible for membership in the Shrine, a Mason had to complete either the Scottish Rite or York Rite systems,[8] but now any Master Mason can join.

In the past, Shriners have practiced hazing rituals as a part of initiating new members: in 1991, a would-be Shriner sued the Oleika Shrine Temple of Lexington, Kentucky over injuries suffered during the hazing, which included being blindfolded and having a jolt of electricity applied to his bare buttocks.[9]

Women's auxiliaries[edit]

While there are plenty of activities for Shriners, there are two organizations tied to the Shrine that are for women only: The Ladies' Oriental Shrine and the Daughters of the Nile. They both support the Shriners Hospitals and promote sociability, and membership in either organization is open to any woman 18 years of age and older who is related to a Shriner or Master Mason by birth or marriage.

The Ladies Oriental Shrine of North America was founded in 1903 in Wheeling, West Virginia,[10] and the Daughters of the Nile was founded in 1913 in Seattle, Washington.[11] The latter organization has locals called "Temples". There were ten of these in 1922. Among the famous members of the Daughters of the Nile was First Lady Florence Harding, wife of Warren G. Harding.[12]

Architecture[edit]

Some of the earliest Shrine Centers often chose a Moorish Revival style for their Temples. Architecturally notable Shriners Temples include the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, the former Mecca Temple, now called New York City Center and used primarily as a concert hall, Newark Symphony Hall, the Landmark Theater (formerly The Mosque) in Richmond, Virginia, the Tripoli Shrine Temple in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the Polly Rosenbaum Building (formerly the El Zaribah Shrine Auditorium) in Phoenix, the Helena Civic Center (Montana) (formerly the Algeria Shrine Temple), Abou Ben Adhem Shrine Mosque in Springfield, Missouri and the Fox Theatre (Atlanta, Georgia) which was jointly built between the Atlanta Shriners and movie mogul William Fox.

Shriners Hospitals for Children[edit]

The Shrine's charitable arm is the Shriners Hospitals for Children, a network of twenty-two hospitals in the United States, Mexico, and Canada.

In June 1920, the Imperial Council Session voted to establish a "Shriners Hospital for Crippled Children." The purpose of this hospital was to treat orthopedic injuries and conditions, diseases, burns, spinal cord injuries, and birth defects, such as cleft lip and palate, in children.[13][14] After much research and debate, the committee chosen to determine the site of the hospital decided there should be not just one hospital but a network of hospitals spread across North America. The first hospital was opened in 1922 in Shreveport, Louisiana, and by the end of the decade 13 more hospitals were in operation.[14] Shriners Hospitals now provide orthopedic care, burn treatment, cleft lip and palate care, and spinal cord injury rehabilitation.

The rules for all of the Shriners Hospitals are simple and to the point: Any child under the age of 18 can be admitted to the hospital if, in the opinion of the doctors, the child can be treated.[14][15] There is no requirement for religion, race, or relationship to a Shriner.

Until June 2012, all care at Shriners Hospitals was provided without charge to patients and their families. At that time, because the size of their endowment had decreased due to losses in the stock market, Shriners Hospitals started billing patients' insurance companies, but still offered free care to children without insurance and waives all out of pocket costs insurance does not cover. Shriners Hospitals for Children is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, meaning that they rely on the generosity of donors to cover the cost of treatment for their patients.[13]

In 2008, Shriners Hospitals had a total budget of $826 million. In 2007 they approved 39,454 new patient applications, and attended to the needs of 125,125 patients.[15] Shriners Hospitals for Children can be found in these cities:[16]

- Boston, MA

- Chicago, IL

- Cincinnati, OH

- Erie, PA*

- Galveston, TX

- Greenville, SC

- Honolulu, HI

- Houston, TX

- Lexington, KY*

- Mexico City, MEX

- Minneapolis, MN

- Montreal, Quebec

- Pasadena, CA*

- Philadelphia, PA

- Portland, OR

- Sacramento, CA

- Salt Lake City, UT

- Shreveport, LA

- Spokane, WA

- Springfield, MA

- St. Louis, MO

- Tampa, FL

*This location is an outpatient, ambulatory care center.[16]

Parade unit[edit]

Most Shrine Temples support several parade units. These units are responsible for promoting a positive Shriner image to the public by participating in local parades. The parade units often include miniature cars powered by lawn mower engines.

An example of a Shrine parade unit is the Heart Shrine Clubs' Original Fire Patrol of Effingham, Illinois. This unit operates miniature fire engines, memorializing a hospital fire that took place in the 1940s in Effingham. They participate in most parades in a 100-mile radius of Effingham. Shriners in Dallas, Texas participate annually in the Twilight Parade at the Texas State Fair.

Shriners in St. Louis have several parade motor units, including miniature cars styled after 1932 Ford coupes and 1970s-era Jeep CJ models, and a unit of miniature Indianapolis-styled race cars. Some of these are outfitted with high-performance, alcohol-fueled engines. The drivers' skills are demonstrated during parades with high-speed spinouts.

Other events[edit]

The Shriners are committed to community service and have been instrumental in countless public projects throughout their domain.

Shriners host the annual East-West Shrine Game, a college football all-star game.

The Shriners originally hosted a golf tournament in association with singer/actor Justin Timberlake, titled the Justin Timberlake Shriners Hospitals for Children Open, a PGA TOUR golf tournament held in Las Vegas, Nevada.[17] The relationship between Timberlake and the Shriners ended in 2012, due to the lack of previously agreed participation on Timberlake's part.[18] In July 2012, The PGA TOUR and Shriners Hospitals for Children announced a five-year title sponsorship extension, carrying the commitment to the Shriners Hospitals for Children Open through 2017.[19] now titled The Shriners Hospitals for Children Open,[20] It is still held in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Once a year, the fraternity meets for the Imperial Council Session in a major North American city. It is not uncommon for these conventions to have 20,000 participants or more, which generates significant revenue for the local economy.

Many Shrine Centers also hold a yearly Shrine Circus as a fundraiser.

See also[edit]

- List of Shrine Centers

- Masonic bodies

- Military Order of the Cootie

- Order of Quetzalcoatl

- Royal Order of Jesters

-----

Statue of Liberty

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Liberty Island Manhattan, New York City, New York,[1] U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°41′21″N 74°2′40″WCoordinates: 40°41′21″N 74°2′40″W |

| Height |

|

| Dedicated | October 28, 1886 |

| Restored | 1938, 1984–1986, 2011–2012 |

| Sculptor | Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi |

| Visitors | 3.2 million (in 2009)[2] |

| Governing body | U.S. National Park Service |

| Website | Statue of Liberty National Monument |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, vi |

| Designated | 1984 (8th session) |

| Reference no. | 307 |

| State Party | United States |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Designated | October 15, 1924 |

| Designated by | President Calvin Coolidge[3] |

| Official name: Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World[4] | |

| Designated | September 14, 2017 |

| Reference no. | 100000829 |

| Designated | May 27, 1971 |

| Reference no. | 1535[5] |

| Type | Individual |

| Designated | September 14, 1976[6] |

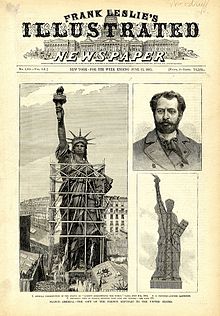

The Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World; French: La Liberté éclairant le monde) is a colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor in New York, in the United States. The copper statue, a gift from the people of France to the people of the United States, was designed by French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and its metal framework was built by Gustave Eiffel. The statue was dedicated on October 28, 1886.

The Statue of Liberty is a figure of Libertas, a robed Roman liberty goddess. She holds a torch above her head with her right hand, and in her left hand carries a tabula ansata inscribed in Roman numerals with "JULY IV MDCCLXXVI" (July 4, 1776), the date of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. A broken shackle and chain lie at her feet as she walks forward, commemorating the recent national abolition of slavery.[7] The statue became an icon of freedom and of the United States, and a national park tourism destination. It is a welcoming sight to immigrants arriving from abroad.

Bartholdi was inspired by a French law professor and politician, Édouard René de Laboulaye, who is said to have commented in 1865 that any monument raised to U.S. independence would properly be a joint project of the French and U.S. peoples. Because of the post-war instability in France, work on the statue did not commence until the early 1870s. In 1875, Laboulaye proposed that the French finance the statue and the U.S. provide the site and build the pedestal. Bartholdi completed the head and the torch-bearing arm before the statue was fully designed, and these pieces were exhibited for publicity at international expositions.

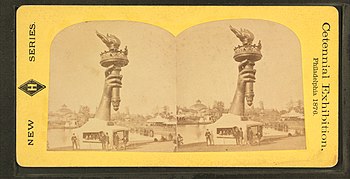

The torch-bearing arm was displayed at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, and in Madison Square Park in Manhattan from 1876 to 1882. Fundraising proved difficult, especially for the Americans, and by 1885 work on the pedestal was threatened by lack of funds. Publisher Joseph Pulitzer, of the New York World, started a drive for donations to finish the project and attracted more than 120,000 contributors, most of whom gave less than a dollar. The statue was built in France, shipped overseas in crates, and assembled on the completed pedestal on what was then called Bedloe's Island. The statue's completion was marked by New York's first ticker-tape parade and a dedication ceremony presided over by President Grover Cleveland.

The statue was administered by the United States Lighthouse Board until 1901 and then by the Department of War; since 1933 it has been maintained by the National Park Service as part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument. Public access to the balcony around the torch has been barred since 1916.

Contents

Design and construction process

Origin

According to the National Park Service, the idea of a monument presented by the French people to the United States was first proposed by Édouard René de Laboulaye, president of the French Anti-Slavery Society and a prominent and important political thinker of his time. The project is traced to a mid-1865 conversation between Laboulaye, a staunch abolitionist, and Frédéric Bartholdi, a sculptor. In after-dinner conversation at his home near Versailles, Laboulaye, an ardent supporter of the Union in the American Civil War, is supposed to have said: "If a monument should rise in the United States, as a memorial to their independence, I should think it only natural if it were built by united effort—a common work of both our nations."[8] The National Park Service, in a 2000 report, however, deemed this a legend traced to an 1885 fundraising pamphlet, and that the statue was most likely conceived in 1870.[9] In another essay on their website, the Park Service suggested that Laboulaye was minded to honor the Union victory and its consequences, "With the abolition of slavery and the Union's victory in the Civil War in 1865, Laboulaye's wishes of freedom and democracy were turning into a reality in the United States. In order to honor these achievements, Laboulaye proposed that a gift be built for the United States on behalf of France. Laboulaye hoped that by calling attention to the recent achievements of the United States, the French people would be inspired to call for their own democracy in the face of a repressive monarchy."[10]

According to sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, who later recounted the story, Laboulaye's alleged comment was not intended as a proposal, but it inspired Bartholdi.[8] Given the repressive nature of the regime of Napoleon III, Bartholdi took no immediate action on the idea except to discuss it with Laboulaye. Bartholdi was in any event busy with other possible projects; in the late 1860s, he approached Isma'il Pasha, Khedive of Egypt, with a plan to build Progress or Egypt Carrying the Light to Asia,[11] a huge lighthouse in the form of an ancient Egyptian female fellah or peasant, robed and holding a torch aloft, at the northern entrance to the Suez Canal in Port Said. Sketches and models were made of the proposed work, though it was never erected. There was a classical precedent for the Suez proposal, the Colossus of Rhodes: an ancient bronze statue of the Greek god of the sun, Helios. This statue is believed to have been over 100 feet (30 m) high, and it similarly stood at a harbor entrance and carried a light to guide ships.[12] Both the khedive and Lesseps declined the proposed statue from Bartholdi, citing the expensive cost.[13] The Port Said Lighthouse was built instead, by François Coignet in 1869.

Any large project was further delayed by the Franco-Prussian War, in which Bartholdi served as a major of militia. In the war, Napoleon III was captured and deposed. Bartholdi's home province of Alsace was lost to the Prussians, and a more liberal republic was installed in France.[8] As Bartholdi had been planning a trip to the United States, he and Laboulaye decided the time was right to discuss the idea with influential Americans.[14] In June 1871, Bartholdi crossed the Atlantic, with letters of introduction signed by Laboulaye.[15]

Arriving at New York Harbor, Bartholdi focused on Bedloe's Island (now named Liberty Island) as a site for the statue, struck by the fact that vessels arriving in New York had to sail past it. He was delighted to learn that the island was owned by the United States government—it had been ceded by the New York State Legislature in 1800 for harbor defense. It was thus, as he put it in a letter to Laboulaye: "land common to all the states."[16] As well as meeting many influential New Yorkers, Bartholdi visited President Ulysses S. Grant, who assured him that it would not be difficult to obtain the site for the statue.[17] Bartholdi crossed the United States twice by rail, and met many Americans who he thought would be sympathetic to the project.[15] But he remained concerned that popular opinion on both sides of the Atlantic was insufficiently supportive of the proposal, and he and Laboulaye decided to wait before mounting a public campaign.[18]

Bartholdi had made a first model of his concept in 1870.[19] The son of a friend of Bartholdi's, U.S. artist John LaFarge, later maintained that Bartholdi made the first sketches for the statue during his U.S. visit at La Farge's Rhode Island studio. Bartholdi continued to develop the concept following his return to France.[19] He also worked on a number of sculptures designed to bolster French patriotism after the defeat by the Prussians. One of these was the Lion of Belfort, a monumental sculpture carved in sandstone below the fortress of Belfort, which during the war had resisted a Prussian siege for over three months. The defiant lion, 73 feet (22 m) long and half that in height, displays an emotional quality characteristic of Romanticism, which Bartholdi would later bring to the Statue of Liberty.[20]

Design, style, and symbolism

Bartholdi and Laboulaye considered how best to express the idea of American liberty.[21] In early American history, two female figures were frequently used as cultural symbols of the nation.[22] One of these symbols, the personified Columbia, was seen as an embodiment of the United States in the manner that Britannia was identified with the United Kingdom and Marianne came to represent France. Columbia had supplanted the traditional European personification of the Americas as an "Indian princess", which had come to be regarded as uncivilized and derogatory toward Americans.[22] The other significant female icon in American culture was a representation of Liberty, derived from Libertas, the goddess of freedom widely worshipped in ancient Rome, especially among emancipated slaves. A Liberty figure adorned most American coins of the time,[21] and representations of Liberty appeared in popular and civic art, including Thomas Crawford's Statue of Freedom (1863) atop the dome of the United States Capitol Building.[21]

Artists of the 18th and 19th centuries striving to evoke republican ideals commonly used representations of Libertas as an allegorical symbol.[21] A figure of Liberty was also depicted on the Great Seal of France.[21] However, Bartholdi and Laboulaye avoided an image of revolutionary liberty such as that depicted in Eugène Delacroix's famed Liberty Leading the People (1830). In this painting, which commemorates France's July Revolution, a half-clothed Liberty leads an armed mob over the bodies of the fallen.[22] Laboulaye had no sympathy for revolution, and so Bartholdi's figure would be fully dressed in flowing robes.[22] Instead of the impression of violence in the Delacroix work, Bartholdi wished to give the statue a peaceful appearance and chose a torch, representing progress, for the figure to hold.[23]

Crawford's statue was designed in the early 1850s. It was originally to be crowned with a pileus, the cap given to emancipated slaves in ancient Rome. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, a Southerner who would later serve as President of the Confederate States of America, was concerned that the pileus would be taken as an abolitionist symbol. He ordered that it be changed to a helmet.[24] Delacroix's figure wears a pileus,[22] and Bartholdi at first considered placing one on his figure as well. Instead, he used a diadem, or crown, to top its head.[25] In so doing, he avoided a reference to Marianne, who invariably wears a pileus.[26] The seven rays form a halo or aureole.[27] They evoke the sun, the seven seas, and the seven continents,[28] and represent another means, besides the torch, whereby Liberty enlightens the world.[23]

Bartholdi's early models were all similar in concept: a female figure in neoclassical style representing liberty, wearing a stola and pella (gown and cloak, common in depictions of Roman goddesses) and holding a torch aloft. According to popular accounts, the face was modeled after that of Charlotte Beysser Bartholdi, the sculptor's mother,[29] but Regis Huber, the curator of the Bartholdi Museum is on record as saying that this, as well as other similar speculations, have no basis in fact.[30] He designed the figure with a strong, uncomplicated silhouette, which would be set off well by its dramatic harbor placement and allow passengers on vessels entering New York Bay to experience a changing perspective on the statue as they proceeded toward Manhattan. He gave it bold classical contours and applied simplified modeling, reflecting the huge scale of the project and its solemn purpose.[23] Bartholdi wrote of his technique:

Bartholdi made alterations in the design as the project evolved. Bartholdi considered having Liberty hold a broken chain, but decided this would be too divisive in the days after the Civil War. The erected statue does stride over a broken chain, half-hidden by her robes and difficult to see from the ground.[25] Bartholdi was initially uncertain of what to place in Liberty's left hand; he settled on a tabula ansata,[32] used to evoke the concept of law.[33] Though Bartholdi greatly admired the United States Constitution, he chose to inscribe "JULY IV MDCCLXXVI" on the tablet, thus associating the date of the country's Declaration of Independence with the concept of liberty.[32]

Bartholdi interested his friend and mentor, architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, in the project.[30] As chief engineer,[30] Viollet-le-Duc designed a brick pier within the statue, to which the skin would be anchored.[34] After consultations with the metalwork foundry Gaget, Gauthier & Co., Viollet-le-Duc chose the metal which would be used for the skin, copper sheets, and the method used to shape it, repoussé, in which the sheets were heated and then struck with wooden hammers.[30][35] An advantage of this choice was that the entire statue would be light for its volume, as the copper need be only 0.094 inches (2.4 mm) thick. Bartholdi had decided on a height of just over 151 feet (46 m) for the statue, double that of Italy's Sancarlone and the German statue of Arminius, both made with the same method.[36]

Announcement and early work

By 1875, France was enjoying improved political stability and a recovering postwar economy. Growing interest in the upcoming Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia led Laboulaye to decide it was time to seek public support.[37] In September 1875, he announced the project and the formation of the Franco-American Union as its fundraising arm. With the announcement, the statue was given a name, Liberty Enlightening the World.[38] The French would finance the statue; Americans would be expected to pay for the pedestal.[39] The announcement provoked a generally favorable reaction in France, though many Frenchmen resented the United States for not coming to their aid during the war with Prussia.[38] French monarchists opposed the statue, if for no other reason than it was proposed by the liberal Laboulaye, who had recently been elected a senator for life.[39] Laboulaye arranged events designed to appeal to the rich and powerful, including a special performance at the Paris Opera on April 25, 1876, that featured a new cantata by composer Charles Gounod. The piece was titled La Liberté éclairant le monde, the French version of the statue's announced name.[38]

Initially focused on the elites, the Union was successful in raising funds from across French society. Schoolchildren and ordinary citizens gave, as did 181 French municipalities. Laboulaye's political allies supported the call, as did descendants of the French contingent in the American Revolutionary War. Less idealistically, contributions came from those who hoped for American support in the French attempt to build the Panama Canal. The copper may have come from multiple sources and some of it is said to have come from a mine in Visnes, Norway,[40] though this has not been conclusively determined after testing samples.[41] According to Cara Sutherland in her book on the statue for the Museum of the City of New York, 200,000 pounds (91,000 kg) was needed to build the statue, and the French copper industrialist Eugène Secrétan donated 128,000 pounds (58,000 kg) of copper.[42]

Although plans for the statue had not been finalized, Bartholdi moved forward with fabrication of the right arm, bearing the torch, and the head. Work began at the Gaget, Gauthier & Co. workshop.[43] In May 1876, Bartholdi traveled to the United States as a member of a French delegation to the Centennial Exhibition,[44] and arranged for a huge painting of the statue to be shown in New York as part of the Centennial festivities.[45] The arm did not arrive in Philadelphia until August; because of its late arrival, it was not listed in the exhibition catalogue, and while some reports correctly identified the work, others called it the "Colossal Arm" or "Bartholdi Electric Light". The exhibition grounds contained a number of monumental artworks to compete for fairgoers' interest, including an outsized fountain designed by Bartholdi.[46] Nevertheless, the arm proved popular in the exhibition's waning days, and visitors would climb up to the balcony of the torch to view the fairgrounds.[47] After the exhibition closed, the arm was transported to New York, where it remained on display in Madison Square Park for several years before it was returned to France to join the rest of the statue.[47]

During his second trip to the United States, Bartholdi addressed a number of groups about the project, and urged the formation of American committees of the Franco-American Union.[48] Committees to raise money to pay for the foundation and pedestal were formed in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia.[49] The New York group eventually took on most of the responsibility for American fundraising and is often referred to as the "American Committee".[50] One of its members was 19-year-old Theodore Roosevelt, the future governor of New York and president of the United States.[48] On March 3, 1877, on his final full day in office, President Grant signed a joint resolution that authorized the President to accept the statue when it was presented by France and to select a site for it. President Rutherford B. Hayes, who took office the following day, selected the Bedloe's Island site that Bartholdi had proposed.[51]

Construction in France

On his return to Paris in 1877, Bartholdi concentrated on completing the head, which was exhibited at the 1878 Paris World's Fair. Fundraising continued, with models of the statue put on sale. Tickets to view the construction activity at the Gaget, Gauthier & Co. workshop were also offered.[52] The French government authorized a lottery; among the prizes were valuable silver plate and a terracotta model of the statue. By the end of 1879, about 250,000 francs had been raised.[53]

The head and arm had been built with assistance from Viollet-le-Duc, who fell ill in 1879. He soon died, leaving no indication of how he intended to transition from the copper skin to his proposed masonry pier.[54] The following year, Bartholdi was able to obtain the services of the innovative designer and builder Gustave Eiffel.[52] Eiffel and his structural engineer, Maurice Koechlin, decided to abandon the pier and instead build an iron truss tower. Eiffel opted not to use a completely rigid structure, which would force stresses to accumulate in the skin and lead eventually to cracking. A secondary skeleton was attached to the center pylon, then, to enable the statue to move slightly in the winds of New York Harbor and as the metal expanded on hot summer days, he loosely connected the support structure to the skin using flat iron bars[30] which culminated in a mesh of metal straps, known as "saddles", that were riveted to the skin, providing firm support. In a labor-intensive process, each saddle had to be crafted individually.[55][56] To prevent galvanic corrosion between the copper skin and the iron support structure, Eiffel insulated the skin with asbestos impregnated with shellac.[57]

Eiffel's design made the statue one of the earliest examples of curtain wall construction, in which the exterior of the structure is not load bearing, but is instead supported by an interior framework. He included two interior spiral staircases, to make it easier for visitors to reach the observation point in the crown.[58] Access to an observation platform surrounding the torch was also provided, but the narrowness of the arm allowed for only a single ladder, 40 feet (12 m) long.[59] As the pylon tower arose, Eiffel and Bartholdi coordinated their work carefully so that completed segments of skin would fit exactly on the support structure.[60] The components of the pylon tower were built in the Eiffel factory in the nearby Parisian suburb of Levallois-Perret.[61]

The change in structural material from masonry to iron allowed Bartholdi to change his plans for the statue's assembly. He had originally expected to assemble the skin on-site as the masonry pier was built; instead he decided to build the statue in France and have it disassembled and transported to the United States for reassembly in place on Bedloe's Island.[62]

In a symbolic act, the first rivet placed into the skin, fixing a copper plate onto the statue's big toe, was driven by United States Ambassador to France Levi P. Morton.[63] The skin was not, however, crafted in exact sequence from low to high; work proceeded on a number of segments simultaneously in a manner often confusing to visitors.[64] Some work was performed by contractors—one of the fingers was made to Bartholdi's exacting specifications by a coppersmith in the southern French town of Montauban.[65] By 1882, the statue was complete up to the waist, an event Barthodi celebrated by inviting reporters to lunch on a platform built within the statue.[66] Laboulaye died in 1883. He was succeeded as chairman of the French committee by Ferdinand de Lesseps, builder of the Suez Canal. The completed statue was formally presented to Ambassador Morton at a ceremony in Paris on July 4, 1884, and de Lesseps announced that the French government had agreed to pay for its transport to New York.[67] The statue remained intact in Paris pending sufficient progress on the pedestal; by January 1885, this had occurred and the statue was disassembled and crated for its ocean voyage.[68]

The committees in the United States faced great difficulties in obtaining funds for the construction of the pedestal. The Panic of 1873 had led to an economic depression that persisted through much of the decade. The Liberty statue project was not the only such undertaking that had difficulty raising money: construction of the obelisk later known as the Washington Monument sometimes stalled for years; it would ultimately take over three-and-a-half decades to complete.[69] There was criticism both of Bartholdi's statue and of the fact that the gift required Americans to foot the bill for the pedestal. In the years following the Civil War, most Americans preferred realistic artworks depicting heroes and events from the nation's history, rather than allegorical works like the Liberty statue.[69] There was also a feeling that Americans should design American public works—the selection of Italian-born Constantino Brumidi to decorate the Capitol had provoked intense criticism, even though he was a naturalized U.S. citizen.[70] Harper's Weekly declared its wish that "M. Bartholdi and our French cousins had 'gone the whole figure' while they were about it, and given us statue and pedestal at once."[71] The New York Times stated that "no true patriot can countenance any such expenditures for bronze females in the present state of our finances."[72] Faced with these criticisms, the American committees took little action for several years.[72]

Design

The foundation of Bartholdi's statue was to be laid inside Fort Wood, a disused army base on Bedloe's Island constructed between 1807 and 1811. Since 1823, it had rarely been used, though during the Civil War, it had served as a recruiting station.[73] The fortifications of the structure were in the shape of an eleven-point star. The statue's foundation and pedestal were aligned so that it would face southeast, greeting ships entering the harbor from the Atlantic Ocean.[74] In 1881, the New York committee commissioned Richard Morris Hunt to design the pedestal. Within months, Hunt submitted a detailed plan, indicating that he expected construction to take about nine months.[75] He proposed a pedestal 114 feet (35 m) in height; faced with money problems, the committee reduced that to 89 feet (27 m).[76]

Hunt's pedestal design contains elements of classical architecture, including Doric portals, as well as some elements influenced by Aztec architecture.[30] The large mass is fragmented with architectural detail, in order to focus attention on the statue.[76] In form, it is a truncated pyramid, 62 feet (19 m) square at the base and 39.4 feet (12.0 m) at the top. The four sides are identical in appearance. Above the door on each side, there are ten disks upon which Bartholdi proposed to place the coats of arms of the states (between 1876 and 1889, there were 38 U.S. states), although this was not done. Above that, a balcony was placed on each side, framed by pillars. Bartholdi placed an observation platform near the top of the pedestal, above which the statue itself rises.[77] According to author Louis Auchincloss, the pedestal "craggily evokes the power of an ancient Europe over which rises the dominating figure of the Statue of Liberty".[76] The committee hired former army General Charles Pomeroy Stone to oversee the construction work.[78] Construction on the 15-foot-deep (4.6 m) foundation began in 1883, and the pedestal's cornerstone was laid in 1884.[75] In Hunt's original conception, the pedestal was to have been made of solid granite. Financial concerns again forced him to revise his plans; the final design called for poured concrete walls, up to 20 feet (6.1 m) thick, faced with granite blocks.[79][80] This Stony Creek granite came from the Beattie Quarry in Branford, Connecticut.[81] The concrete mass was the largest poured to that time.[80]

Norwegian immigrant civil engineer Joachim Goschen Giæver designed the structural framework for the Statue of Liberty. His work involved design computations, detailed fabrication and construction drawings, and oversight of construction. In completing his engineering for the statue's frame, Giæver worked from drawings and sketches produced by Gustave Eiffel.[82]

Fundraising

Fundraising for the statue had begun in 1882. The committee organized a large number of money-raising events.[83] As part of one such effort, an auction of art and manuscripts, poet Emma Lazarus was asked to donate an original work. She initially declined, stating she could not write a poem about a statue. At the time, she was also involved in aiding refugees to New York who had fled anti-Semitic pogroms in eastern Europe. These refugees were forced to live in conditions that the wealthy Lazarus had never experienced. She saw a way to express her empathy for these refugees in terms of the statue.[84] The resulting sonnet, "The New Colossus", including the iconic lines: "Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free", is uniquely identified with the Statue of Liberty and is inscribed on a plaque in its museum.[85]

Even with these efforts, fundraising lagged. Grover Cleveland, the governor of New York, vetoed a bill to provide $50,000 for the statue project in 1884. An attempt the next year to have Congress provide $100,000, sufficient to complete the project, also failed. The New York committee, with only $3,000 in the bank, suspended work on the pedestal. With the project in jeopardy, groups from other American cities, including Boston and Philadelphia, offered to pay the full cost of erecting the statue in return for relocating it.[86]

Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World, a New York newspaper, announced a drive to raise $100,000—the equivalent of $2.3 million today.[87] Pulitzer pledged to print the name of every contributor, no matter how small the amount given.[88] The drive captured the imagination of New Yorkers, especially when Pulitzer began publishing the notes he received from contributors. "A young girl alone in the world" donated "60 cents, the result of self denial."[89] One donor gave "five cents as a poor office boy's mite toward the Pedestal Fund." A group of children sent a dollar as "the money we saved to go to the circus with."[90] Another dollar was given by a "lonely and very aged woman."[89] Residents of a home for alcoholics in New York's rival city of Brooklyn—the cities would not merge until 1898—donated $15; other drinkers helped out through donation boxes in bars and saloons.[91] A kindergarten class in Davenport, Iowa, mailed the World a gift of $1.35.[89] As the donations flooded in, the committee resumed work on the pedestal.[92]

Construction

On June 17, 1885, the French steamer Isère arrived in New York with the crates holding the disassembled statue on board. New Yorkers displayed their new-found enthusiasm for the statue. Two hundred thousand people lined the docks and hundreds of boats put to sea to welcome the ship.[93][94] After five months of daily calls to donate to the statue fund, on August 11, 1885, the World announced that $102,000 had been raised from 120,000 donors, and that 80 percent of the total had been received in sums of less than one dollar.[95]

Even with the success of the fund drive, the pedestal was not completed until April 1886. Immediately thereafter, reassembly of the statue began. Eiffel's iron framework was anchored to steel I-beams within the concrete pedestal and assembled.[96] Once this was done, the sections of skin were carefully attached.[97] Due to the width of the pedestal, it was not possible to erect scaffolding, and workers dangled from ropes while installing the skin sections. Nevertheless, no one died during the construction.[98] Bartholdi had planned to put floodlights on the torch's balcony to illuminate it; a week before the dedication, the Army Corps of Engineers vetoed the proposal, fearing that ships' pilots passing the statue would be blinded. Instead, Bartholdi cut portholes in the torch—which was covered with gold leaf—and placed the lights inside them.[99] A power plant was installed on the island to light the torch and for other electrical needs.[100] After the skin was completed, renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, co-designer of Manhattan's Central Park and Brooklyn's Prospect Park, supervised a cleanup of Bedloe's Island in anticipation of the dedication.[101]

Dedication

A ceremony of dedication was held on the afternoon of October 28, 1886. President Grover Cleveland, the former New York governor, presided over the event.[102] On the morning of the dedication, a parade was held in New York City; estimates of the number of people who watched it ranged from several hundred thousand to a million. President Cleveland headed the procession, then stood in the reviewing stand to see bands and marchers from across America. General Stone was the grand marshal of the parade. The route began at Madison Square, once the venue for the arm, and proceeded to the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan by way of Fifth Avenue and Broadway, with a slight detour so the parade could pass in front of the World building on Park Row. As the parade passed the New York Stock Exchange, traders threw ticker tape from the windows, beginning the New York tradition of the ticker-tape parade.[103]

A nautical parade began at 12:45 p.m., and President Cleveland embarked on a yacht that took him across the harbor to Bedloe's Island for the dedication.[104] De Lesseps made the first speech, on behalf of the French committee, followed by the chairman of the New York committee, Senator William M. Evarts. A French flag draped across the statue's face was to be lowered to unveil the statue at the close of Evarts's speech, but Bartholdi mistook a pause as the conclusion and let the flag fall prematurely. The ensuing cheers put an end to Evarts's address.[103] President Cleveland spoke next, stating that the statue's "stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man's oppression until Liberty enlightens the world".[105] Bartholdi, observed near the dais, was called upon to speak, but he declined. Orator Chauncey M. Depew concluded the speechmaking with a lengthy address.[106]

No members of the general public were permitted on the island during the ceremonies, which were reserved entirely for dignitaries. The only females granted access were Bartholdi's wife and de Lesseps's granddaughter; officials stated that they feared women might be injured in the crush of people. The restriction offended area suffragists, who chartered a boat and got as close as they could to the island. The group's leaders made speeches applauding the embodiment of Liberty as a woman and advocating women's right to vote.[105] A scheduled fireworks display was postponed until November 1 because of poor weather.[107]

Shortly after the dedication, The Cleveland Gazette, an African American newspaper, suggested that the statue's torch not be lit until the United States became a free nation "in reality":

After dedication

Lighthouse Board and War Department (1886–1933)

When the torch was illuminated on the evening of the statue's dedication, it produced only a faint gleam, barely visible from Manhattan. The World characterized it as "more like a glowworm than a beacon."[100] Bartholdi suggested gilding the statue to increase its ability to reflect light, but this proved too expensive. The United States Lighthouse Board took over the Statue of Liberty in 1887 and pledged to install equipment to enhance the torch's effect; in spite of its efforts, the statue remained virtually invisible at night. When Bartholdi returned to the United States in 1893, he made additional suggestions, all of which proved ineffective. He did successfully lobby for improved lighting within the statue, allowing visitors to better appreciate Eiffel's design.[100] In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt, once a member of the New York committee, ordered the statue's transfer to the War Department, as it had proved useless as a lighthouse.[109] A unit of the Army Signal Corps was stationed on Bedloe's Island until 1923, after which military police remained there while the island was under military jurisdiction.[110]

The statue rapidly became a landmark. Many immigrants who entered through New York saw it as a welcoming sight. Oral histories of immigrants record their feelings of exhilaration on first viewing the Statue of Liberty. One immigrant who arrived from Greece recalled:

Originally, the statue was a dull copper color, but shortly after 1900 a green patina, also called verdigris, caused by the oxidation of the copper skin, began to spread. As early as 1902 it was mentioned in the press; by 1906 it had entirely covered the statue.[112] Believing that the patina was evidence of corrosion, Congress authorized US$62,800 (equivalent to $1,751,000 in 2018) for various repairs, and to paint the statue both inside and out.[113] There was considerable public protest against the proposed exterior painting.[114] The Army Corps of Engineers studied the patina for any ill effects to the statue and concluded that it protected the skin, "softened the outlines of the Statue and made it beautiful."[115] The statue was painted only on the inside. The Corps of Engineers also installed an elevator to take visitors from the base to the top of the pedestal.[115]

On July 30, 1916, during World War I, German saboteurs set off a disastrous explosion on the Black Tom peninsula in Jersey City, New Jersey, in what is now part of Liberty State Park, close to Bedloe's Island. Carloads of dynamite and other explosives that were being sent to Britain and France for their war efforts were detonated, and seven people were killed. The statue sustained minor damage, mostly to the torch-bearing right arm, and was closed for ten days. The cost to repair the statue and buildings on the island was about $100,000 (equivalent to about $2,300,000 in 2018). The narrow ascent to the torch was closed for public-safety reasons, and it has remained closed ever since.[106]

That same year, Ralph Pulitzer, who had succeeded his father Joseph as publisher of the World, began a drive to raise $30,000 (equivalent to $691,000 in 2018) for an exterior lighting system to illuminate the statue at night. He claimed over 80,000 contributors, but failed to reach the goal. The difference was quietly made up by a gift from a wealthy donor—a fact that was not revealed until 1936. An underwater power cable brought electricity from the mainland and floodlights were placed along the walls of Fort Wood. Gutzon Borglum, who later sculpted Mount Rushmore, redesigned the torch, replacing much of the original copper with stained glass. On December 2, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson pressed the telegraph key that turned on the lights, successfully illuminating the statue.[116]

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, images of the statue were heavily used in both recruitment posters and the Liberty bond drives that urged American citizens to support the war financially. This impressed upon the public the war's stated purpose—to secure liberty—and served as a reminder that embattled France had given the United States the statue.[117]

In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge used his authority under the Antiquities Act to declare the statue a national monument.[109] The only successful suicide in the statue's history occurred five years later, when a man climbed out of one of the windows in the crown and jumped to his death, glancing off the statue's breast and landing on the base.[118]

Early National Park Service years (1933–1982)

In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the statue to be transferred to the National Park Service (NPS). In 1937, the NPS gained jurisdiction over the rest of Bedloe's Island.[109] With the Army's departure, the NPS began to transform the island into a park.[119] The Works Progress Administration (WPA) demolished most of the old buildings, regraded and reseeded the eastern end of the island, and built granite steps for a new public entrance to the statue from its rear. The WPA also carried out restoration work within the statue, temporarily removing the rays from the statue's halo so their rusted supports could be replaced. Rusted cast-iron steps in the pedestal were replaced with new ones made of reinforced concrete;[120] the upper parts of the stairways within the statue were replaced, as well. Copper sheathing was installed to prevent further damage from rainwater that had been seeping into the pedestal.[121] The statue was closed to the public from May until December 1938.[120]

During World War II, the statue remained open to visitors, although it was not illuminated at night due to wartime blackouts. It was lit briefly on December 31, 1943, and on D-Day, June 6, 1944, when its lights flashed "dot-dot-dot-dash", the Morse code for V, for victory. New, powerful lighting was installed in 1944–1945, and beginning on V-E Day, the statue was once again illuminated after sunset. The lighting was for only a few hours each evening, and it was not until 1957 that the statue was illuminated every night, all night.[122] In 1946, the interior of the statue within reach of visitors was coated with a special plastic so that graffiti could be washed away.[121]

In 1956, an Act of Congress officially renamed Bedloe's Island as Liberty Island, a change advocated by Bartholdi generations earlier. The act also mentioned the efforts to found an American Museum of Immigration on the island, which backers took as federal approval of the project, though the government was slow to grant funds for it.[123] Nearby Ellis Island was made part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument by proclamation of President Lyndon Johnson in 1965.[109] In 1972, the immigration museum, in the statue's base, was finally opened in a ceremony led by President Richard Nixon. The museum's backers never provided it with an endowment to secure its future and it closed in 1991 after the opening of an immigration museum on Ellis Island.[96]

In 1970, Ivy Bottini led a demonstration at the statue where she and others from the National Organization for Women's New York chapter draped an enormous banner over a railing which read "WOMEN OF THE WORLD UNITE!"[124][125]

Beginning December 26, 1971, 15 anti-Vietnam War veterans occupied the statue, flying a US flag upside down from her crown. They left December 28 following a Federal Court order.[126] The statue was also several times taken over briefly by demonstrators publicizing causes such as Puerto Rican independence, opposition to abortion, and opposition to US intervention in Grenada. Demonstrations with the permission of the Park Service included a Gay Pride Parade rally and the annual Captive Baltic Nations rally.[127]

A powerful new lighting system was installed in advance of the American Bicentennial in 1976. The statue was the focal point for Operation Sail, a regatta of tall ships from all over the world that entered New York Harbor on July 4, 1976, and sailed around Liberty Island.[128] The day concluded with a spectacular display of fireworks near the statue.[129]

Renovation and rededication (1982–2000)

The statue was examined in great detail by French and American engineers as part of the planning for its centennial in 1986.[130] In 1982, it was announced that the statue was in need of considerable restoration. Careful study had revealed that the right arm had been improperly attached to the main structure. It was swaying more and more when strong winds blew and there was a significant risk of structural failure. In addition, the head had been installed 2 feet (0.61 m) off center, and one of the rays was wearing a hole in the right arm when the statue moved in the wind. The armature structure was badly corroded, and about two percent of the exterior plates needed to be replaced.[131] Although problems with the armature had been recognized as early as 1936, when cast iron replacements for some of the bars had been installed, much of the corrosion had been hidden by layers of paint applied over the years.[132]

In May 1982, President Ronald Reagan announced the formation of the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Centennial Commission, led by Chrysler Corporation chair Lee Iacocca, to raise the funds needed to complete the work.[133][134][135] Through its fundraising arm, the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., the group raised more than $350 million in donations for the renovations of both the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.[136] The Statue of Liberty was one of the earliest beneficiaries of a cause marketing campaign. A 1983 promotion advertised that for each purchase made with an American Express card, the company would contribute one cent to the renovation of the statue. The campaign generated contributions of $1.7 million to the restoration project.[137]

In 1984, the statue was closed to the public for the duration of the renovation. Workers erected the world's largest free-standing scaffold,[30] which obscured the statue from view. Liquid nitrogen was used to remove layers of paint that had been applied to the interior of the copper skin over decades, leaving two layers of coal tar, originally applied to plug leaks and prevent corrosion. Blasting with baking soda powder removed the tar without further damaging the copper.[138] The restorers' work was hampered by the asbestos-based substance that Bartholdi had used—ineffectively, as inspections showed—to prevent galvanic corrosion. Workers within the statue had to wear protective gear, dubbed "moon suits", with self-contained breathing circuits.[139] Larger holes in the copper skin were repaired, and new copper was added where necessary.[140] The replacement skin was taken from a copper rooftop at Bell Labs, which had a patina that closely resembled the statue's; in exchange, the laboratory was provided some of the old copper skin for testing.[141] The torch, found to have been leaking water since the 1916 alterations, was replaced with an exact replica of Bartholdi's unaltered torch.[142] Consideration was given to replacing the arm and shoulder; the National Park Service insisted that they be repaired instead.[143] The original torch was removed and replaced in 1986 with the current one, whose flame is covered in 24-karat gold.[33] The torch reflects the Sun's rays in daytime and is lighted by floodlights at night.[33]

The entire puddled iron armature designed by Gustave Eiffel was replaced. Low-carbon corrosion-resistant stainless steel bars that now hold the staples next to the skin are made of Ferralium, an alloy that bends slightly and returns to its original shape as the statue moves.[144] To prevent the ray and arm making contact, the ray was realigned by several degrees.[145] The lighting was again replaced—night-time illumination subsequently came from metal-halide lamps that send beams of light to particular parts of the pedestal or statue, showing off various details.[146] Access to the pedestal, which had been through a nondescript entrance built in the 1960s, was renovated to create a wide opening framed by a set of monumental bronze doors with designs symbolic of the renovation.[147] A modern elevator was installed, allowing handicapped access to the observation area of the pedestal.[148] An emergency elevator was installed within the statue, reaching up to the level of the shoulder.[149]

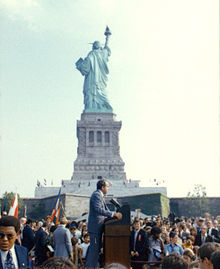

July 3–6, 1986, was designated "Liberty Weekend", marking the centennial of the statue and its reopening. President Reagan presided over the rededication, with French President François Mitterrand in attendance. July 4 saw a reprise of Operation Sail,[150] and the statue was reopened to the public on July 5.[151] In Reagan's dedication speech, he stated, "We are the keepers of the flame of liberty; we hold it high for the world to see."[150]

Closures and reopenings (2001–present)

Immediately following the September 11 attacks, the statue and Liberty Island were closed to the public. The island reopened at the end of 2001, while the pedestal and statue remained off-limits. The pedestal reopened in August 2004,[151] but the National Park Service announced that visitors could not safely be given access to the statue due to the difficulty of evacuation in an emergency. The Park Service adhered to that position through the remainder of the Bush administration.[152] New York Congressman Anthony Weiner made the statue's reopening a personal crusade.[153] On May 17, 2009, President Barack Obama's Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar, announced that as a "special gift" to America, the statue would be reopened to the public as of July 4, but that only a limited number of people would be permitted to ascend to the crown each day.[152]

The statue, including the pedestal and base, closed on October 29, 2011, for installation of new elevators and staircases and to bring other facilities, such as restrooms, up to code. The statue was reopened on October 28, 2012,[1][154][155] but then closed again a day later in advance of Hurricane Sandy.[156] Although the storm did not harm the statue, it destroyed some of the infrastructure on both Liberty and Ellis Islands, including the dock used by the ferries that ran to Liberty and Ellis Islands. On November 8, 2012, a Park Service spokesperson announced that both islands would remain closed for an indefinite period for repairs to be done.[157] Since Liberty Island had no electricity, a generator was installed to power temporary floodlights to illuminate the statue at night. The superintendent of Statue of Liberty National Monument, David Luchsinger—whose home on the island was severely damaged—stated that it would be "optimistically ... months" before the island was reopened to the public.[158] The statue and Liberty Island reopened to the public on July 4, 2013.[159] Ellis Island remained closed for repairs for several more months but reopened in late October 2013.[160]

The Statue of Liberty has also been closed due to government shutdowns and protests. During the October 2013 United States federal government shutdown, Liberty Island and other federally funded sites were closed.[161] In addition, Liberty Island was briefly closed on July 4, 2018, after a woman protesting against American immigration policy climbed onto the statue.[162]

On October 7, 2016, construction started on the new Statue of Liberty Museum on Liberty Island.[163] The new $70 million, 26,000-square-foot (2,400 m2) museum may be visited by all who come to the island,[164] as opposed to the museum in the pedestal, which only 20% of the island's visitors had access to.[163] The new museum, designed by FXFOWLE Architects, is integrated with the surrounding parkland.[165][166] Diane von Fürstenberg headed the fundraising for the museum, and the project received over $40 million in fundraising by groundbreaking.[165] The museum opened on May 16, 2019.[167][168]

Access and attributes

Location and access

The statue is situated in Upper New York Bay on Liberty Island south of Ellis Island, which together comprise the Statue of Liberty National Monument. Both islands were ceded by New York to the federal government in 1800.[169] As agreed in an 1834 compact between New York and New Jersey that set the state border at the bay's midpoint, the original islands remain New York territory though located on the New Jersey side of the state line. Liberty Island is one of the islands that are part of the borough of Manhattan in New York. Land created by reclamation added to the 2.3-acre (0.93 ha) original island at Ellis Island is New Jersey territory.[170]

No charge is made for entrance to the national monument, but there is a cost for the ferry service that all visitors must use,[171] as private boats may not dock at the island. A concession was granted in 2007 to Statue Cruises to operate the transportation and ticketing facilities, replacing Circle Line, which had operated the service since 1953.[172] The ferries, which depart from Liberty State Park in Jersey City and the Battery in Lower Manhattan, also stop at Ellis Island when it is open to the public, making a combined trip possible.[173] All ferry riders are subject to security screening, similar to airport procedures, prior to boarding.[174]

Visitors intending to enter the statue's base and pedestal must obtain a complimentary museum/pedestal ticket along with their ferry ticket.[171][175] Those wishing to climb the staircase within the statue to the crown purchase a special ticket, which may be reserved up to a year in advance. A total of 240 people per day are permitted to ascend: ten per group, three groups per hour. Climbers may bring only medication and cameras—lockers are provided for other items—and must undergo a second security screening.[176]

Inscriptions, plaques, and dedications

There are several plaques and dedicatory tablets on or near the Statue of Liberty.

- A plaque on the copper just under the figure in front declares that it is a colossal statue representing Liberty, designed by Bartholdi and built by the Paris firm of Gaget, Gauthier et Cie (Cie is the French abbreviation analogous to Co.). [177]

- A presentation tablet, also bearing Bartholdi's name, declares the statue is a gift from the people of the Republic of France that honors "the Alliance of the two Nations in achieving the Independence of the United States of America and attests their abiding friendship."[177]

- A tablet placed by the American Committee commemorates the fundraising done to build the pedestal.[177]

- The cornerstone bears a plaque placed by the Freemasons.[177]

- In 1903, a bronze tablet that bears the text of Emma Lazarus's sonnet, "The New Colossus" (1883), was presented by friends of the poet. Until the 1986 renovation, it was mounted inside the pedestal; later, it resided in the Statue of Liberty Museum, in the base.[177]

- "The New Colossus" tablet is accompanied by a tablet given by the Emma Lazarus Commemorative Committee in 1977, celebrating the poet's life.[177]

A group of statues stands at the western end of the island, honoring those closely associated with the Statue of Liberty. Two Americans—Pulitzer and Lazarus—and three Frenchmen—Bartholdi, Eiffel, and Laboulaye—are depicted. They are the work of Maryland sculptor Phillip Ratner.[178]

Historical designations

President Calvin Coolidge officially designated the Statue of Liberty as part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1924.[3][179] The monument was expanded to also include Ellis Island in 1965.[180][181] The following year, the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island were jointly added to the National Register of Historic Places,[182] and the statue individually in 2017.[4] On the sub-national level, the Statue of Liberty was added to the New Jersey Register of Historic Places in 1971,[5] and was made a New York City designated landmark in 1976.[6]

In 1984, the Statue of Liberty was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The UNESCO "Statement of Significance" describes the statue as a "masterpiece of the human spirit" that "endures as a highly potent symbol—inspiring contemplation, debate and protest—of ideals such as liberty, peace, human rights, abolition of slavery, democracy and opportunity."[183]

Physical characteristics

| Feature[74] | Imperial | Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Height of copper statue | 151 ft 1 in | 46 m |

| Foundation of pedestal (ground level) to tip of torch | 305 ft 1 in | 93 m |

| Heel to top of head | 111 ft 1 in | 34 m |

| Height of hand | 16 ft 5 in | 5 m |

| Index finger | 8 ft 1 in | 2.44 m |

| Circumference at second joint | 3 ft 6 in | 1.07 m |

| Head from chin to cranium | 17 ft 3 in | 5.26 m |

| Head thickness from ear to ear | 10 ft 0 in | 3.05 m |

| Distance across the eye | 2 ft 6 in | 0.76 m |

| Length of nose | 4 ft 6 in | 1.48 m |

| Right arm length | 42 ft 0 in | 12.8 m |

| Right arm greatest thickness | 12 ft 0 in | 3.66 m |

| Thickness of waist | 35 ft 0 in | 10.67 m |

| Width of mouth | 3 ft 0 in | 0.91 m |

| Tablet, length | 23 ft 7 in | 7.19 m |

| Tablet, width | 13 ft 7 in | 4.14 m |

| Tablet, thickness | 2 ft 0 in | 0.61 m |

| Height of pedestal | 89 ft 0 in | 27.13 m |

| Height of foundation | 65 ft 0 in | 19.81 m |

| Weight of copper used in statue | 60,000 pounds | 27.22 tonnes |

| Weight of steel used in statue | 250,000 pounds | 113.4 tonnes |

| Total weight of statue | 450,000 pounds | 204.1 tonnes |

| Thickness of copper sheeting | 3/32 of an inch | 2.4 mm |

Depictions

Hundreds of replicas of the Statue of Liberty are displayed worldwide.[184] A smaller version of the statue, one-fourth the height of the original, was given by the American community in Paris to that city. It now stands on the Île aux Cygnes, facing west toward her larger sister.[184] A replica 30 feet (9.1 m) tall stood atop the Liberty Warehouse on West 64th Street in Manhattan for many years;[184] it now resides at the Brooklyn Museum.[185] In a patriotic tribute, the Boy Scouts of America, as part of their Strengthen the Arm of Liberty campaign in 1949–1952, donated about two hundred replicas of the statue, made of stamped copper and 100 inches (2.5 m) in height, to states and municipalities across the United States.[186] Though not a true replica, the statue known as the Goddess of Democracy temporarily erected during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 was similarly inspired by French democratic traditions—the sculptors took care to avoid a direct imitation of the Statue of Liberty.[187] Among other recreations of New York City structures, a replica of the statue is part of the exterior of the New York-New York Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas.[188]

As an American icon, the Statue of Liberty has been depicted on the country's coinage and stamps. It appeared on commemorative coins issued to mark its 1986 centennial, and on New York's 2001 entry in the state quarters series.[189] An image of the statue was chosen for the American Eagle platinum bullion coins in 1997, and it was placed on the reverse, or tails, side of the Presidential Dollar series of circulating coins.[28] Two images of the statue's torch appear on the current ten-dollar bill.[190] The statue's intended photographic depiction on a 2010 forever stamp proved instead to be of the replica at the Las Vegas casino.[191]

Depictions of the statue have been used by many regional institutions. Between 1986[192] and 2000,[193] New York State issued license plates with an outline of the statue.[192][193] The Women's National Basketball Association's New York Liberty use both the statue's name and its image in their logo, in which the torch's flame doubles as a basketball.[194] The New York Rangers of the National Hockey League depicted the statue's head on their third jersey, beginning in 1997.[195] The National Collegiate Athletic Association's 1996 Men's Basketball Final Four, played at New Jersey's Meadowlands Sports Complex, featured the statue in its logo.[196] The Libertarian Party of the United States uses the statue in its emblem.[197]

The statue is a frequent subject in popular culture. In music, it has been evoked to indicate support for American policies, as in Toby Keith's song "Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American)", and in opposition, appearing on the cover of the Dead Kennedys' album Bedtime for Democracy, which protested the Reagan administration.[198] In film, the torch is the setting for the climax of director Alfred Hitchcock's 1942 movie Saboteur.[199] The statue makes one of its most famous cinematic appearances in the 1968 picture Planet of the Apes, in which it is seen half-buried in sand.[198][200] It is knocked over in the science-fiction film Independence Day [201] and in Cloverfield the head is ripped off.[202] In Jack Finney's time-travel novel Time and Again, the right arm of the statue, on display in the early 1880s in Madison Square Park, plays a crucial role.[203] Robert Holdstock, consulting editor of The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, wondered in 1979:

See also

- List of the tallest statues in the United States

- Place des États-Unis, in Paris, France

- Statues and sculptures in New York City

- The Statue of Liberty (film), 1985 Ken Burns documentary film

- List of statues by height

-----

Kaaba

| (Kaʿbah) | |

|---|---|

كَعْبَة

| |

The Kaaba surrounded by pilgrims

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Great Mosque of Mecca, Mecca, Hejaz, Saudi Arabia |

| Geographic coordinates | 21°25′21.0″N 39°49′34.2″ECoordinates: 21°25′21.0″N 39°49′34.2″E |

| Height (max) | 13.1 m (43 ft) |

The Kaaba (Arabic: كَعْبَة kaʿbah IPA: [kaʕba], "Cube"), also referred to as al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah (Arabic: ٱلْكَعْبَة ٱلْمُشَرَّفَة, the Holy Ka'bah), is a building at the center of Islam's most important mosque, Great Mosque of Mecca (Arabic: ٱلْمَسْجِد ٱلْحَرَام, The Sacred Mosque), in the Hejazi city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia.[1] It is the most sacred site in Islam.[2] It is considered by Muslims to be the Bayt Allāh (Arabic: بَيْت ٱلله, "House of God"), and has a similar role to the Tabernacle and Holy of Holies in Judaism. Its location determines the qiblah (Arabic: قِبْلَة, direction of prayer). Wherever they are in the world, Muslims are expected to face the Kaaba when performing Salah, the Islamic prayer.

One of the Five Pillars of Islam requires every Muslim who is able to do so to perform the Hajj (Arabic: حَجّ, Greater Pilgrimage) at least once in their lifetime. Multiple parts of the hajj require pilgrims to make Tawaf (Arabic: طَوَاف, Circumambulation) seven times counter-clockwise around the Kaaba, the first three times fast, at the edge of the courtyard, and the last four times slowly, nearer the Kaaba. Tawaf is also performed by pilgrims during the ‘Umrah (Arabic: عُمْرَة, Lesser Pilgrimage).[2] However, the most significant time is during the hajj, when millions of pilgrims gather to circle the building during a 5-day period.[3][4] In 2017, the number of pilgrims coming from outside the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to perform hajj was officially reported as 1,752,014 and 600,108 Saudi Arabian residents bringing the total number of pilgrims to 2,352,122.[5]

Contents

Lexicology[edit]

The literal meaning of the Arabic word kaʿbah (كَعْبَة) is 'cube'.[6] In the Quran, the Kaaba is also mentioned as al-bayt (Arabic: البیت "the house") and baytī (Arabic: بیتی "My house") [2:125, 22:26], al-bayt al-ḥarām (Arabic: البیت الحرام "The Sacred House") [5:97], al-bayt al-ʿatīq (Arabic: البیت العتیق "The Ancient House") [22:29,33], and baytika al-muḥarram (Arabic: بیتك المحرم "your inviolable house"). The mosque surrounding the Kaaba is called al-Masjid al-Haram ("The Sacred Mosque").

Architecture and interior[edit]

The Kaaba is a cuboid stone structure made of granite. It is approximately 13.1 m (43 ft) high (some claim 12.03 m (39.5 ft)), with sides measuring 11.03 m (36.2 ft) by 12.86 m (42.2 ft).[7][8] Inside the Kaaba, the floor is made of marble and limestone. The interior walls, measuring 13 m (43 ft) by 9 m (30 ft), are clad with tiled, white marble halfway to the roof, with darker trimmings along the floor. The floor of the interior stands about 2.2 m (7.2 ft) above the ground area where tawaf is performed.

The wall directly adjacent to the entrance of the Kaaba has six tablets inlaid with inscriptions, and there are several more tablets along the other walls. Along the top corners of the walls runs a green cloth embroidered with gold Qur'anic verses. Caretakers anoint the marble cladding with the same scented oil used to anoint the Black Stone outside. Three pillars (some erroneously report two) stand inside the Kaaba, with a small altar or table set between one and the other two. (It has been claimed that this table is used for the placement of perfumes or other items.) Lamp-like objects (possible lanterns or crucible censers) hang from the ceiling. The ceiling itself is of a darker colour, similar in hue to the lower trimming. A golden door—the bāb al-tawbah (also romanized as Baabut Taubah, and meaning "Door of Repentance")—on the right wall (right of the entrance) opens to an enclosed staircase that leads to a hatch, which itself opens to the roof. Both the roof and ceiling (collectively dual-layered) are made of stainless steel-capped teak wood.

Each numbered item in the following list corresponds to features noted in the diagram image.

- Al-Ḥajaru al-Aswad, "the Black Stone", is located on the Kaaba's eastern corner. Its northern corner is known as the Ruknu l-ˤĪrāqī, "the Iraqi corner", its western as the Ruknu sh-Shāmī, "the Levantine corner", and its southern as Ruknu l-Yamanī, "the Yemeni corner" taught by Imam Ali.[2][8] The four corners of the Kaaba roughly point toward the four cardinal directions of the compass.[2] Its major (long) axis is aligned with the rising of the star Canopus toward which its southern wall is directed, while its minor axis (its east-west facades) roughly align with the sunrise of summer solstice and the sunset of winter solstice.[9][10]

- The entrance is a door set 2.13 m (7 ft) above the ground on the north-eastern wall of the Kaaba, which acts as the façade.[2] In 1979 the 300 kg gold doors made by chief artist Ahmad bin Ibrahim Badr, replaced the old silver doors made by his father, Ibrahim Badr in 1942.[11] There is a wooden staircase on wheels, usually stored in the mosque between the arch-shaped gate of Banū Shaybah and the Zamzam Well. The oldest door that still survives dates back to 1045 CE.[12]

- Mīzāb al-Raḥmah, rainwater spout made of gold. Added in the rebuilding of 1627 after the previous year's rain caused three of the four walls to collapse.

- Gutter, added in 1627 to protect the foundation from groundwater.

- Hatīm (also romanized as hateem), a low wall originally part of the Kaaba. It is a semi-circular wall opposite, but not connected to, the north-west wall of the Kaaba. This is 131 cm (52 in) in height and 1.5 m (4.9 ft) in width, and is composed of white marble. At one time the space lying between the hatīm and the Kaaba belonged to the Kaaba itself, and for this reason it is not entered during the tawaf.

- Al-Multazam, the roughly 2 m (6.6 ft) space along the wall between the Black Stone and the entry door. It is sometimes considered pious or desirable for a hajji to touch this area of the Kaaba, or perform dua here.

- The Station of Ibrahim (Maqam Ibrahim), a glass and metal enclosure with what is said to be an imprint of Abraham's feet. Ibrahim is said to have stood on this stone during the construction of the upper parts of the Kaaba, raising Ismail on his shoulders for the uppermost parts.[13]

- Corner of the Black Stone (East).