Spoke 5: The Biblewheel and The 5th Century

(Go back to main Menu)

Jerome

Jerome lived from the 2nd half of the 4th to the 5th century. His life reflects the 4th and 5th Spokes on the Biblewheel, meaning the 4th book Numbers and the 5th book of the 2nd Cycle of the Biblewheel Daniel. He does mention the wilderness as in the 4th book of Numbers but also mentions his diet of not eating pulse and spending time with lions as did Daniel the 5th book of the 2nd cycle of the Biblewheel.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerome

(Go back to main Menu)

Jerome

Jerome lived from the 2nd half of the 4th to the 5th century. His life reflects the 4th and 5th Spokes on the Biblewheel, meaning the 4th book Numbers and the 5th book of the 2nd Cycle of the Biblewheel Daniel. He does mention the wilderness as in the 4th book of Numbers but also mentions his diet of not eating pulse and spending time with lions as did Daniel the 5th book of the 2nd cycle of the Biblewheel.

Spoke 5: The Life of Jerome from the 5th century reflects the 5th Spoke of the Biblewheel, which consist of the 3 books Deuteronomy/Daniel/Ephesians.

Rome was sacked in 410 AD. Jerome had written of the clergy of his time and their corruptions. Deuteronomy mentioned a foreign nation invading in Deuteronomy 32. Ephesians 5 mentioned that the wrath of God will come down on the children of disobedience. And Daniel 5 showed that the disobedient king of Babylon, the city was invaded by the Medes and the Persians.

Notice that Jerome is the same as Jeremiah, which also means Yeremiahu or God has lifted or exalted. It has the word Ram or Rome in his name. It's the same word found in Abram.

Speaking of Rome, notice that the city was founded by Romulus (more than his brother Remus):

And the last emperor in the 5th century was Romulus Augustus:

The city starts with a Romulus and ends with a Romulus. The same applies in the east. It was founded by Constantine the Great and ended by Constantine XI in 1453. And Constantine means "constant" or "continuing".

https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/632826185165480121

Jerome

| Saint Jerome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hermit and Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | c. 27 March 347 Stridon (possibly Strido Dalmatiae, on the border of Dalmatia and Pannonia) |

| Died | 30 September 420 (aged c. 73)[1] Bethlehem, Palaestina Prima |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church Anglican Communion Lutheranism Oriental Orthodoxy |

| Major shrine | Basilica of Saint Mary Major, Rome, Italy |

| Feast | 30 September (Western Christianity) 15 June (Eastern Christianity) |

| Attributes | lion, cardinal attire, cross, skull, trumpet, owl, books and writing material |

| Patronage | archeologists; archivists; Bible scholars; librarians; libraries; school children; students; translators; Morong, Rizal |

| Major works | The Vulgate De viris illustribus Chronicon |

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

Aquinas, Scotus, and Ockham

|

| Ethics |

| Schools |

| Philosophers |

|

|

Jerome (/dʒəˈroʊm/; Latin: Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; Greek: Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; c. 27 March 347 – 30 September 420) was a priest, confessor, theologian, and historian. He was born at Stridon, a village near Emona on the border of Dalmatia and Pannonia.[3][4][5] He is best known for his translation of most of the Bible into Latin (the translation that became known as the Vulgate), and his commentaries on the Gospels. His list of writings is extensive.[6]

The protégé of Pope Damasus I, who died in December of 384, Jerome was known for his teachings on Christian moral life, especially to those living in cosmopolitan centers such as Rome. In many cases, he focused his attention on the lives of women and identified how a woman devoted to Jesus should live her life. This focus stemmed from his close patron relationships with several prominent female ascetics who were members of affluent senatorial families.[7]

He is recognised as a Saint and Doctor of the Church by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Lutheran Church, and the Anglican Communion.[8] His feast day is 30 September.

Life

Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus was born at Stridon around 347[9] He was of Illyrian ancestry and his native tongue was the Illyrian dialect.[10][11] He was not baptized until about 360–366, when he had gone to Rome with his friend Bonosus (who may or may not have been the same Bonosus whom Jerome identifies as his friend who went to live as a hermit on an island in the Adriatic) to pursue rhetorical and philosophical studies. He studied under the grammarian Aelius Donatus. There Jerome learned Latin and at least some Greek,[12] though probably not the familiarity with Greek literature he would later claim to have acquired as a schoolboy.[13]

As a student in Rome, he engaged in the superficial escapades and homosexual behaviour of students there, which he indulged in quite casually but for which he suffered terrible bouts of guilt afterwards.[14] To appease his conscience, he would visit on Sundays the sepulchres of the martyrs and the Apostles in the catacombs. This experience would remind him of the terrors of hell:

Jerome used a quote from Virgil—"On all sides round horror spread wide; the very silence breathed a terror on my soul"[18]—to describe the horror of hell. Jerome initially used classical authors to describe Christian concepts such as hell that indicated both his classical education and his deep shame of their associated practices, such as pederasty which was found in Rome. Although initially skeptical of Christianity, he was eventually converted.[19]After several years in Rome, he travelled with Bonosus to Gaul and settled in Trier where he seems to have first taken up theological studies, and where he copied, for his friend Tyrannius Rufinus, Hilary of Poitiers' commentary on the Psalms and the treatise De synodis. Next came a stay of at least several months, or possibly years, with Rufinus at Aquileia, where he made many Christian friends.

Some of these accompanied him when he set out about 373 on a journey through Thrace and Asia Minor into northern Syria. At Antioch, where he stayed the longest, two of his companions died and he himself was seriously ill more than once. During one of these illnesses (about the winter of 373–374), he had a vision that led him to lay aside his secular studies and devote himself to God. He seems to have abstained for a considerable time from the study of the classics and to have plunged deeply into that of the Bible, under the impulse of Apollinaris of Laodicea, then teaching in Antioch and not yet suspected of heresy.

Seized with a desire for a life of ascetic penance, he went for a time to the desert of Chalcis, to the southeast of Antioch, known as the "Syrian Thebaid", from the number of hermits inhabiting it. During this period, he seems to have found time for studying and writing. He made his first attempt to learn Hebrew under the guidance of a converted Jew; and he seems to have been in correspondence with Jewish Christians in Antioch. Around this time he had copied for him a Hebrew Gospel, of which fragments are preserved in his notes, and is known today as the Gospel of the Hebrews, and which the Nazarenes considered to be the true Gospel of Matthew.[20] Jerome translated parts of this Hebrew Gospel into Greek.[21]

Returning to Antioch in 378 or 379, he was ordained by Bishop Paulinus, apparently unwillingly and on condition that he continue his ascetic life. Soon afterward, he went to Constantinople to pursue a study of Scripture under Gregory Nazianzen. He seems to have spent two years there, then left, and the next three (382–385) he was in Rome again, as secretary to Pope Damasus I and the leading Roman Christians. Invited originally for the synodof 382, held to end the schism of Antioch as there were rival claimants to be the proper patriarch in Antioch. Jerome had accompanied one of the claimants, Paulinus back to Rome in order to get more support for him, and distinguished himself to the pope, and took a prominent place in his councils.

He was given duties in Rome, and he undertook a revision of the Latin Bible, to be based on the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. He also updated the Psalter containing the Book of Psalms then at use in Rome based on the Septuagint. Though he did not realize it yet, translating much of what became the Latin Vulgate Bible would take many years and be his most important achievement (see Writings– Translations section below).

In Rome he was surrounded by a circle of well-born and well-educated women, including some from the noblest patrician families, such as the widows Lea, Marcella and Paula, with Paula's daughters Blaesilla and Eustochium. The resulting inclination of these women towards the monastic life, away from the indulgent lasciviousness in Rome, and his unsparing criticism of the secular clergy of Rome, brought a growing hostility against him among the Roman clergy and their supporters. Soon after the death of his patron Damasus (10 December 384), Jerome was forced by them to leave his position at Rome after an inquiry was brought up by the Roman clergy into allegations that he had an improper relationship with the widow Paula. Still, his writings were highly regarded by women who were attempting to maintain a vow of becoming a consecrated virgin. His letters were widely read and distributed throughout the Christian empire and it is clear through his writing that he knew these virgin women were not his only audience.[7]

Additionally, his condemnation of Blaesilla's hedonistic lifestyle in Rome had led her to adopt ascetic practices, but it affected her health and worsened her physical weakness to the point that she died just four months after starting to follow his instructions; much of the Roman populace were outraged at Jerome for causing the premature death of such a lively young woman, and his insistence to Paula that Blaesilla should not be mourned, and complaints that her grief was excessive, were seen as heartless, polarising Roman opinion against him.[23]

In August 385, he left Rome for good and returned to Antioch, accompanied by his brother Paulinian and several friends, and followed a little later by Paula and Eustochium, who had resolved to end their days in the Holy Land. In the winter of 385, Jerome acted as their spiritual adviser. The pilgrims, joined by Bishop Paulinus of Antioch, visited Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and the holy places of Galilee, and then went to Egypt, the home of the great heroes of the ascetic life.

At the Catechetical School of Alexandria, Jerome listened to the catechist Didymus the Blind expounding the prophet Hosea and telling his reminiscences of Anthony the Great, who had died 30 years before; he spent some time in Nitria, admiring the disciplined community life of the numerous inhabitants of that "city of the Lord", but detecting even there "concealed serpents", i.e., the influence of Origen of Alexandria. Late in the summer of 388 he was back in Palestine, and spent the remainder of his life working in a cave near Bethlehem, the very cave Jesus was born,[24]surrounded by a few friends, both men and women (including Paula and Eustochium), to whom he acted as priestly guide and teacher.

Amply provided by Paula with the means of livelihood and of increasing his collection of books, he led a life of incessant activity in literary production. To these last 34 years of his career belong the most important of his works; his version of the Old Testament from the original Hebrew text, the best of his scriptural commentaries, his catalogue of Christian authors, and the dialogue against the Pelagians, the literary perfection of which even an opponent recognized. To this period also belong most of his polemics, which distinguished him among the orthodox Fathers, including the treatises against the Origenism later declared anathema, of Bishop John II of Jerusalem and his early friend Rufinus. Later, as a result of his writings against Pelagianism, a body of excited partisans broke into the monastic buildings, set them on fire, attacked the inmates and killed a deacon, forcing Jerome to seek safety in a neighboring fortress (416).

It is recorded that Jerome died near Bethlehem on 30 September 420. The date of his death is given by the Chronicon of Prosper of Aquitaine. His remains, originally buried at Bethlehem, are said to have been later transferred to the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, though other places in the West claim some relics—the cathedral at Nepi boasting possession of his head, which, according to another tradition, is in the Escorial.

Translation of the Bible (382-405)

Jerome was a scholar at a time when that statement implied a fluency in Greek. He knew some Hebrew when he started his translation project, but moved to Jerusalem to strengthen his grip on Jewish scripture commentary. A wealthy Roman aristocrat, Paula, funded his stay in a monastery in Bethlehem and he completed his translation there. He began in 382 by correcting the existing Latin language version of the New Testament, commonly referred to as the Vetus Latina. By 390 he turned to translating the Hebrew Bible from the original Hebrew, having previously translated portions from the Septuagint which came from Alexandria. He believed that the mainstream Rabbinical Judaism had rejected the Septuagint as invalid Jewish scriptural texts because of what were ascertained as mistranslations along with its Hellenistic heretical elements.[25] He completed this work by 405. Prior to Jerome's Vulgate, all Latin translations of the Old Testament were based on the Septuagint, not the Hebrew. Jerome's decision to use a Hebrew text instead of the previous translated Septuagint went against the advice of most other Christians, including Augustine, who thought the Septuagint inspired. Modern scholarship, however, has sometimes cast doubts on the actual quality of Jerome's Hebrew knowledge. Many modern scholars believe that the Greek Hexapla is the main source for Jerome's "iuxta Hebraeos" translation of the Old Testament.[26] However, detailed studies have shown that to a considerable degree Jerome was a competent Hebraist.[27]

Commentaries (405-420)

For the next 15 years, until he died, Jerome produced a number of commentaries on Scripture, often explaining his translation choices in using the original Hebrew rather than suspect translations. His patristic commentaries align closely with Jewish tradition, and he indulges in allegorical and mystical subtleties after the manner of Philo and the Alexandrian school. Unlike his contemporaries, he emphasizes the difference between the Hebrew Bible "apocrypha" and the Hebraica veritas of the protocanonical books. In his Vulgate's prologues, he describes some portions of books in the Septuagint that were not found in the Hebrew as being non-canonical (he called them apocrypha);[28] for Baruch, he mentions by name in his Prologue to Jeremiah and notes that it is neither read nor held among the Hebrews, but does not explicitly call it apocryphal or "not in the canon".[29] His Preface to The Books of Samuel and Kings[30] includes the following statement, commonly called the Helmeted Preface:

Although Jerome was once suspicious of the apocrypha, it is said that he later viewed them as Scripture. For example, in Jerome's letter to Eustochium he quotes Sirach 13:2,[31] elsewhere Jerome also refers to Baruch, the Story of Susannah and Wisdom as scripture.[32][33][34]

Jerome's commentaries fall into three groups:

- His translations or recastings of Greek predecessors, including fourteen homilies on the Book of Jeremiah and the same number on the Book of Ezekiel by Origen (translated ca. 380 in Constantinople); two homilies of Origen of Alexandria on the Song of Solomon (in Rome, ca. 383); and thirty-nine on the Gospel of Luke (ca. 389, in Bethlehem). The nine homilies of Origen on the Book of Isaiah included among his works were not done by him. Here should be mentioned, as an important contribution to the topography of Palestine, his book De situ et nominibus locorum Hebraeorum, a translation with additions and some regrettable omissions of the Onomasticon of Eusebius. To the same period (ca. 390) belongs the Liber interpretationis nominum Hebraicorum, based on a work supposed to go back to Philo and expanded by Origen.

- Original commentaries on the Old Testament. To the period before his settlement at Bethlehem and the following five years belong a series of short Old Testament studies: De seraphim, De voce Osanna, De tribus quaestionibus veteris legis (usually included among the letters as 18, 20, and 36); Quaestiones hebraicae in Genesim; Commentarius in Ecclesiasten; Tractatus septem in Psalmos 10–16 (lost); Explanationes in Michaeam, Sophoniam, Nahum, Habacuc, Aggaeum. After 395 he composed a series of longer commentaries, though in rather a desultory fashion: first on Jonah and Obadiah (396), then on Isaiah (ca. 395-ca. 400), on Zechariah, Malachi, Hoseah, Joel, Amos (from 406), on the Book of Daniel (ca. 407), on Ezekiel (between 410 and 415), and on Jeremiah (after 415, left unfinished).

- New Testament commentaries. These include only Philemon, Galatians, Ephesians, and Titus (hastily composed 387–388); Matthew (dictated in a fortnight, 398); Mark, selected passages in Luke, Revelation, and the prologue to the Gospel of John.

Historical and hagiographic writings

Jerome is also known as a historian. One of his earliest historical works was his Chronicle (or Chronicon or Temporum liber), composed ca. 380 in Constantinople; this is a translation into Latin of the chronological tables which compose the second part of the Chronicon of Eusebius, with a supplement covering the period from 325 to 379. Despite numerous errors taken over from Eusebius, and some of his own, Jerome produced a valuable work, if only for the impulse which it gave to such later chroniclers as Prosper, Cassiodorus, and Victor of Tunnuna to continue his annals.

Of considerable importance as well is the De viris illustribus, which was written at Bethlehem in 392, the title and arrangement of which are borrowed from Suetonius. It contains short biographical and literary notes on 135 Christian authors, from Saint Peter down to Jerome himself. For the first seventy-eight authors Eusebius (Historia ecclesiastica) is the main source; in the second section, beginning with Arnobius and Lactantius, he includes a good deal of independent information, especially as to western writers.

Four works of a hagiographic nature are:

- the Vita Pauli monachi, written during his first sojourn at Antioch (ca. 376), the legendary material of which is derived from Egyptian monastic tradition;

- the Vitae Patrum (Vita Pauli primi eremitae), a biography of Saint Paul of Thebes;

- the Vita Malchi monachi captivi (ca. 391), probably based on an earlier work, although it purports to be derived from the oral communications of the aged ascetic Malchus of Syria originally made to him in the desert of Chalcis;

- the Vita Hilarionis, of the same date, containing more trustworthy historical matter than the other two, and based partly on the biography of Epiphanius and partly on oral tradition.

The so-called Martyrologium Hieronymianum is spurious; it was apparently composed by a western monk toward the end of the 6th or beginning of the 7th century, with reference to an expression of Jerome's in the opening chapter of the Vita Malchi, where he speaks of intending to write a history of the saints and martyrs from the apostolic times.

Saint Jerome's description of vitamin A deficiency

Letters

Jerome's letters or epistles, both by the great variety of their subjects and by their qualities of style, form an important portion of his literary remains. Whether he is discussing problems of scholarship, or reasoning on cases of conscience, comforting the afflicted, or saying pleasant things to his friends, scourging the vices and corruptions of the time and against sexual immorality among the clergy,[36] exhorting to the ascetic life and renunciation of the world, or breaking a lance with his theological opponents, he gives a vivid picture not only of his own mind, but of the age and its peculiar characteristics. Because there was no distinct line between personal documents and those meant for publication, we frequently find in his letters both confidential messages and treatises meant for others besides the one to whom he was writing.[37]

Due to the time he spent in Rome among wealthy families belonging to the Roman upper-class, Jerome was frequently commissioned by women who had taken a vow of virginity to write them in guidance of how to live their life. As a result, he spent a great deal of his life corresponding to these women about certain abstentions and lifestyle practices.[7] These included the clothing she should wear, the interactions she should undertake and how to go about conducting herself during such interactions, and what and how she ate and drank. The letters most frequently reprinted or referred to are of a hortatory nature, such as Ep. 14, Ad Heliodorum de laude vitae solitariae; Ep. 22, Ad Eustochium de custodia virginitatis; Ep. 52, Ad Nepotianum de vita clericorum et monachorum, a sort of epitome of pastoral theology from the ascetic standpoint; Ep. 53, Ad Paulinum de studio scripturarum; Ep. 57, to the same, De institutione monachi; Ep. 70, Ad Magnum de scriptoribus ecclesiasticis; and Ep. 107, Ad Laetam de institutione filiae.

- Letter to Dardanus (Ep. 129)

Theological writings

Practically all of Jerome's productions in the field of dogma have a more or less vehemently polemical character, and are directed against assailants of the orthodox doctrines. Even the translation of the treatise of Didymus the Blindon the Holy Spirit into Latin (begun in Rome 384, completed at Bethlehem) shows an apologetic tendency against the Arians and Pneumatomachoi. The same is true of his version of Origen's De principiis (ca. 399), intended to supersede the inaccurate translation by Rufinus. The more strictly polemical writings cover every period of his life. During the sojourns at Antioch and Constantinople he was mainly occupied with the Arian controversy, and especially with the schisms centering around Meletius of Antioch and Lucifer Calaritanus. Two letters to Pope Damasus (15 and 16) complain of the conduct of both parties at Antioch, the Meletians and Paulinians, who had tried to draw him into their controversy over the application of the terms ousia and hypostasis to the Trinity. At the same time or a little later (379) he composed his Liber Contra Luciferianos, in which he cleverly uses the dialogue form to combat the tenets of that faction, particularly their rejection of baptism by heretics.

In Rome (ca. 383) he wrote a passionate counterblast against the teaching of Helvidius, in defense of the doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary and of the superiority of the single over the married state. An opponent of a somewhat similar nature was Jovinianus, with whom he came into conflict in 392 (Adversus Jovinianum, Against Jovinianus) and the defense of this work addressed to his friend Pammachius, numbered 48 in the letters). Once more he defended the ordinary practices of piety and his own ascetic ethics in 406 against the Gallic presbyter Vigilantius, who opposed the cultus of martyrs and relics, the vow of poverty, and clerical celibacy. Meanwhile, the controversy with John II of Jerusalem and Rufinus concerning the orthodoxy of Origen occurred. To this period belong some of his most passionate and most comprehensive polemical works: the Contra Joannem Hierosolymitanum(398 or 399); the two closely connected Apologiae contra Rufinum (402); and the "last word" written a few months later, the Liber tertius seuten ultima responsio adversus scripta Rufini. The last of his polemical works is the skilfully composed Dialogus contra Pelagianos (415).

Reception by later Christianity

Jerome is the second most voluminous writer (after Augustine of Hippo) in ancient Latin Christianity. In the Catholic Church, he is recognized as the patron saint of translators, librarians and encyclopedists.[41]

He acquired a knowledge of Hebrew by studying with a Jew who converted to Christianity, and took the unusual position (for that time) that the Hebrew, and not the Septuagint, was the inspired text of the Old Testament. The traditional view is that he used this knowledge to translate what became known as the Vulgate, and his translation was slowly but eventually accepted in the Catholic Church.[42] The later resurgence of Hebrew studies within Christianity owes much to him.

He showed more zeal and interest in the ascetic ideal than in abstract speculation. It was this strict asceticism that made Martin Luther judge him so severely. In fact, Protestant readers are not generally inclined to accept his writings as authoritative. The tendency to recognize a superior comes out in his correspondence with Augustine (cf. Jerome's letters numbered 56, 67, 102–105, 110–112, 115–116; and 28, 39, 40, 67–68, 71–75, 81–82 in Augustine's).[citation needed]

Despite the criticisms already mentioned, Jerome has retained a rank among the western Fathers. This would be his due, if for nothing else, on account of the great influence exercised by his Latin version of the Bible upon the subsequent ecclesiastical and theological development.[43]

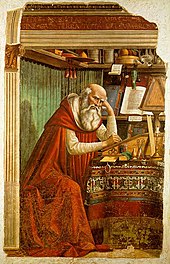

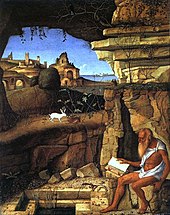

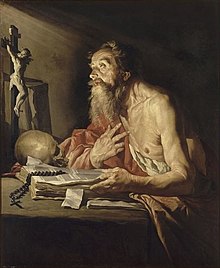

In art

In art, Jerome is often represented as one of the four Latin doctors of the Church along with Augustine of Hippo, Ambrose, and Pope Gregory I. As a prominent member of the Roman clergy, he has often been portrayed anachronistically in the garb of a cardinal. Even when he is depicted as a half-clad anchorite, with cross, skull and Bible for the only furniture of his cell, the red hat or some other indication of his rank as cardinal is as a rule introduced somewhere in the picture.

During Jerome's life, cardinals did not exist. However, by the time of the Renaissance and the Baroque it was common practice for a secretary to the pope to be a cardinal (as Jerome had effectively been to Damasus), and so this was reflected in artistic interpretations.

He is also often depicted with a lion, in reference to the popular hagiographical belief that Jerome had tamed a lion in the wilderness by healing its paw. The source for the story may actually have been the second century Roman tale of Androcles, or confusion with the exploits of Saint Gerasimus (Jerome in later Latin is "Geronimus").[44][45][46] Hagiographies of Jerome talk of his having spent many years in the Syrian desert, and artists often depict him in a "wilderness", which for West European painters can take the form of a wood or forest.[47]

From the late Middle Ages, depictions of him in a wider setting became popular. He is either shown in his study, surrounded by books and the equipment of a scholar, or in a rocky desert, or in a setting that combines both themes, with him studying a book under the shelter of a rock-face or cave mouth. His attribute of the lion, often shown at a smaller scale, may be beside him in either setting.

The saint is often depicted in connection with the vanitas motif, the reflection on the meaninglessness of earthly life and the transient nature of all earthly goods and pursuits. In the 16th century Saint Jerome in his study by Pieter Coecke van Aelst and workshop the saint is depicted with a skull. Behind him on the wall is pinned an admonition, Cogita Mori (Think upon death). Further reminders of the vanitas motif of the passage of time and the imminence of death are the image of the Last Judgment visible in the saint's Bible, the candle and the hourglass.[48]

He is also sometimes depicted with an owl, the symbol of wisdom and scholarship.[49] Writing materials and the trumpet of final judgment are also part of his iconography.[49] He is commemorated on 30 September with a memorial.

See also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerome

| Comparing Daniel with the 5th Century |

|

|---|---|

| Daniel 1 - Listen

1 In the third year of the reign of Jehoiakim king of Judah came Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon unto Jerusalem, and besieged it. 2 And the Lord gave Jehoiakim king of Judah into his hand, with part of the vessels of the house of God: which he carried into the land of Shinar to the house of his god; and he brought the vessels into the treasure house of his god. 3 And the king spake unto Ashpenaz the master of his eunuchs, that he should bring [certain] of the children of Israel, and of the king's seed, and of the princes; 4 Children in whom [was] no blemish, but well favoured, and skilful in all wisdom, and cunning in knowledge, and understanding science, and such as [had] ability in them to stand in the king's palace, and whom they might teach the learning and the tongue of the Chaldeans. 5 And the king appointed them a daily provision of the king's meat, and of the wine which he drank: so nourishing them three years, that at the end thereof they might stand before the king. 6 Now among these were of the children of Judah, Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah: 7 Unto whom the prince of the eunuchs gave names: for he gave unto Daniel [the name] of Belteshazzar; and to Hananiah, of Shadrach; and to Mishael, of Meshach; and to Azariah, of Abednego. 8 But Daniel purposed in his heart that he would not defile himself with the portion of the king's meat, nor with the wine which he drank: therefore he requested of the prince of the eunuchs that he might not defile himself. 9 Now God had brought Daniel into favour and tender love with the prince of the eunuchs. 10 And the prince of the eunuchs said unto Daniel, I fear my lord the king, who hath appointed your meat and your drink: for why should he see your faces worse liking than the children which [are] of your sort? then shall ye make [me] endanger my head to the king. 11 Then said Daniel to Melzar, whom the prince of the eunuchs had set over Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah, 12 Prove thy servants, I beseech thee, ten days; and let them give us pulse to eat, and water to drink. 13 Then let our countenances be looked upon before thee, and the countenance of the children that eat of the portion of the king's meat: and as thou seest, deal with thy servants. 14 So he consented to them in this matter, and proved them ten days. 15 And at the end of ten days their countenances appeared fairer and fatter in flesh than all the children which did eat the portion of the king's meat. 16 Thus Melzar took away the portion of their meat, and the wine that they should drink; and gave them pulse. 17 As for these four children, God gave them knowledge and skill in all learning and wisdom: and Daniel had understanding in all visions and dreams. 18 Now at the end of the days that the king had said he should bring them in, then the prince of the eunuchs brought them in before Nebuchadnezzar. 19 And the king communed with them; and among them all was found none like Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah: therefore stood they before the king. 20 And in all matters of wisdom [and] understanding, that the king enquired of them, he found them ten times better than all the magicians [and] astrologers that [were] in all his realm. 21 And Daniel continued [even] unto the first year of king Cyrus. |

|

| Comparing Daniel with the 5th Century |

|

|---|---|

| Daniel 6 - Listen 1 It pleased Darius to set over the kingdom an hundred and twenty princes, which should be over the whole kingdom; 2 And over these three presidents; of whom Daniel [was] first: that the princes might give accounts unto them, and the king should have no damage. 3 Then this Daniel was preferred above the presidents and princes, because an excellent spirit [was] in him; and the king thought to set him over the whole realm. 4 Then the presidents and princes sought to find occasion against Daniel concerning the kingdom; but they could find none occasion nor fault; forasmuch as he [was] faithful, neither was there any error or fault found in him. 5 Then said these men, We shall not find any occasion against this Daniel, except we find [it] against him concerning the law of his God. 6 Then these presidents and princes assembled together to the king, and said thus unto him, King Darius, live for ever. 7 All the presidents of the kingdom, the governors, and the princes, the counsellors, and the captains, have consulted together to establish a royal statute, and to make a firm decree, that whosoever shall ask a petition of any God or man for thirty days, save of thee, O king, he shall be cast into the den of lions. 8 Now, O king, establish the decree, and sign the writing, that it be not changed, according to the law of the Medes and Persians, which altereth not. 9 Wherefore king Darius signed the writing and the decree. 10 Now when Daniel knew that the writing was signed, he went into his house; and his windows being open in his chamber toward Jerusalem, he kneeled upon his knees three times a day, and prayed, and gave thanks before his God, as he did aforetime. 11 Then these men assembled, and found Daniel praying and making supplication before his God. 12 Then they came near, and spake before the king concerning the king's decree; Hast thou not signed a decree, that every man that shall ask [a petition] of any God or man within thirty days, save of thee, O king, shall be cast into the den of lions? The king answered and said, The thing [is] true, according to the law of the Medes and Persians, which altereth not. 13 Then answered they and said before the king, That Daniel, which [is] of the children of the captivity of Judah, regardeth not thee, O king, nor the decree that thou hast signed, but maketh his petition three times a day. 14 Then the king, when he heard [these] words, was sore displeased with himself, and set [his] heart on Daniel to deliver him: and he laboured till the going down of the sun to deliver him. 15 Then these men assembled unto the king, and said unto the king, Know, O king, that the law of the Medes and Persians [is], That no decree nor statute which the king establisheth may be changed. 16 Then the king commanded, and they brought Daniel, and cast [him] into the den of lions. [Now] the king spake and said unto Daniel, Thy God whom thou servest continually, he will deliver thee. 17 And a stone was brought, and laid upon the mouth of the den; and the king sealed it with his own signet, and with the signet of his lords; that the purpose might not be changed concerning Daniel. 18 Then the king went to his palace, and passed the night fasting: neither were instruments of musick brought before him: and his sleep went from him. 19 Then the king arose very early in the morning, and went in haste unto the den of lions. 20 And when he came to the den, he cried with a lamentable voice unto Daniel: [and] the king spake and said to Daniel, O Daniel, servant of the living God, is thy God, whom thou servest continually, able to deliver thee from the lions? 21 Then said Daniel unto the king, O king, live for ever. 22 My God hath sent his angel, and hath shut the lions' mouths, that they have not hurt me: forasmuch as before him innocency was found in me; and also before thee, O king, have I done no hurt. 23 Then was the king exceeding glad for him, and commanded that they should take Daniel up out of the den. So Daniel was taken up out of the den, and no manner of hurt was found upon him, because he believed in his God. 24 And the king commanded, and they brought those men which had accused Daniel, and they cast [them] into the den of lions, them, their children, and their wives; and the lions had the mastery of them, and brake all their bones in pieces or ever they came at the bottom of the den. 25 Then king Darius wrote unto all people, nations, and languages, that dwell in all the earth; Peace be multiplied unto you. 26 I make a decree, That in every dominion of my kingdom men tremble and fear before the God of Daniel: for he [is] the living God, and stedfast for ever, and his kingdom [that] which shall not be destroyed, and his dominion [shall be even] unto the end. 27 He delivereth and rescueth, and he worketh signs and wonders in heaven and in earth, who hath delivered Daniel from the power of the lions. 28 So this Daniel prospered in the reign of Darius, and in the reign of Cyrus the Persian. |

|

![Biblewheel: A wise king scattereth the wicked, and bringeth the wheel over them. [Pro 20:26 KJV]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiFT6-YCyrSoMjVlsXjQIWJVHaMXsChgqmAIk9mLeNmsgqWXD94k5TOPejvnORdnQ39OL3U4FleKWbC1r46q2t5nYnipb_qDZFNHQR_YXesnm6ucYt2g1DjbBhXnZmML3IHhunsYSeRBU/s1600-r/biblewheel_traced_edited.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment