Spoke 18: The Biblewheel and The 18th Century

(Go back to main Menu)The Present Banking System

“Gentlemen! I too have been a close observer of the doings of the Bank of the United States. I have had men watching you for a long time, and am convinced that you have used the funds of the bank to speculate in the breadstuffs of the country. When you won, you divided the profits amongst you, and when you lost, you charged it to the bank. You tell me that if I take the deposits from the bank and annul its charter I shall ruin ten thousand families. That may be true, gentlemen, but that is your sin! Should I let you go on, you will ruin fifty thousand families, and that would be my sin! You are a den of vipers and thieves. I have determined to rout you out, and by the Eternal, (bringing his fist down on the table) I will rout you out!”

Bank War

| Bank War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

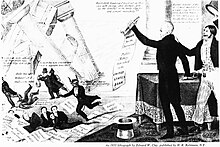

Cartoon depicting the political conflict between Andrew Jackson and Nicholas Biddle over the Second Bank of the United States | |||

| Date | 1832–1836[1] | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shutdown of the Bank and its replacement by state banks.

The Second Bank of the United States was established as a private organization with a 20-year charter, having the exclusive right to conduct banking on a national scale. The goal behind the B.U.S. was to stabilize the American economy by establishing a uniform currency and strengthening the federal government. Supporters of the Bank regarded it as a stabilizing force in the economy due to its ability to smooth out variations in prices and trade, extend credit, supply the nation with a sound and uniform currency, provide fiscal services for the treasury department, facilitate long-distance trade, and prevent inflation by regulating the lending practices of state banks.[2] Jacksonian Democrats cited instances of corruption and alleged that the B.U.S. favored merchants and speculators at the expense of farmers and artisans, appropriated public money for risky private investments and interference in politics, and conferred economic privileges on a small group of stockholders and financial elites, thereby violating the principle of equal opportunity. Some found the Bank's public–private organization to be unconstitutional, and argued that the institution's charter violated state sovereignty. To them, the Bank symbolized corruption while threatening liberty.

In early 1832, the president of the B.U.S., Nicholas Biddle, in alliance with the National Republicans under Senators Henry Clay (Kentucky) and Daniel Webster (Massachusetts), submitted an application for a renewal of the Bank's twenty-year charter four years before the charter was set to expire, intending to pressure Jackson into making a decision prior to the 1832 presidential election, in which Jackson would face Clay. When Congress voted to reauthorize the Bank, Jackson vetoed the bill. His veto message was a polemical declaration of the social philosophy of the Jacksonian movement that pitted "the planters, the farmers, the mechanic and the laborer" against the "monied interest".[3] The B.U.S. became the central issue that divided the Jacksonians from the National Republicans. Although the Bank provided significant financial assistance to Clay and pro-B.U.S. newspaper editors, Jackson secured an overwhelming election victory.

Fearing economic reprisals from Biddle, Jackson swiftly removed the Bank's federal deposits. In 1833, he arranged to distribute the funds to dozens of state banks. The new Whig Party emerged in opposition to his perceived abuse of executive power, officially censuring Jackson in the Senate. In an effort to promote sympathy for the institution's survival, Biddle retaliated by contracting Bank credit, inducing a mild financial downturn. A reaction set in throughout America’s financial and business centers against Biddle's maneuvers, compelling the Bank to reverse its tight money policies, but its chances of being rechartered were all but finished. The economy did extremely well during Jackson's time as president, but his economic policies, including his war against the Bank, are sometimes blamed for contributing to the Panic of 1837.

Resurrection of a national banking system[edit]

The First Bank of the United States was established at the direction of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton in 1791. Hamilton supported the foundation of a national bank because he believed that it would increase the authority and influence of the federal government, effectively manage trade and commerce, strengthen the national defense, and pay the debt. It was subject to attacks from agrarians and constructionists led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. They believed that it was unconstitutional because the Constitution did not expressly allow for it, would infringe on the rights of the states, and would benefit a small group while delivering no advantage to the many, especially farmers. Hamilton's view won out and the Bank was created.[4] More states and localities began to charter their own banks. State banks printed their own notes which were sometimes used out-of-state, and this encouraged other states to establish banks in order to compete.[5] The bank, as established, acted as a source of credit for the US government, and as the only chartered interstate bank, but lacked the powers of a modern central bank: It did not set monetary policy, regulate private banks, hold their excess reserves, could not print fiat money (only coin money backed by its capitalization), or act as a lender of last resort.[6]

President Madison and Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin supported recharter of the First Bank in 1811. They cited "expediency" and "necessity," not principle. Opponents of the Bank defeated recharter by a single vote in both the House and Senate in 1811.[7] State banks opposed recharter of the national bank because when state bank notes were deposited with the First Bank of the United States, the Bank would present these notes to state banks and demand gold in exchange, which limited the state banks' ability to issue notes and maintain adequate reserves of specie, or hard money. At that time, bank notes could be exchanged for a fixed value of gold or silver.[8]

The arguments in favor of reviving a national system of finance, as well as internal improvements and protective tariffs, were prompted by national security concerns during the War of 1812.[9] The chaos of the war had, according to some, "demonstrated the absolute necessity of a national banking system".[10] The push for the creation of a new national bank occurred during the post-war period of American history known as the Era of Good Feelings. There was a strong movement to increase the power of the federal government. Some people blamed a weak central government for America's poor performance during much of the War of 1812. Humiliated by its opposition to the war, the Federalist Party, founded by Hamilton, collapsed. Nearly all politicians joined the Republican Party, founded by Jefferson. It was hoped that the disappearance of the Federalist Party would mark the end of party politics. But even in the new single party system, ideological and sectional differences began to flare up once again over several issues, one of them being the campaign to recharter the Bank.[11]

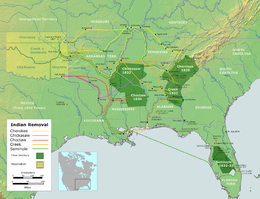

In 1815, Secretary of State James Monroe told President Madison that a national bank "would attach the commercial part of the community in a much greater degree to the Government [and] interest them in its operations…This is the great desideratum [essential objective] of our system."[12] Support for this "national system of money and finance" grew with the post-war economy and land boom, uniting the interests of eastern financiers with southern and western Republican nationalists. The roots for the resurrection of the Bank of the United States lay fundamentally in the transformation of America from a simple agrarian economy to one that was becoming interdependent with finance and industry.[13][14] Vast western lands were opening for white settlement,[15] accompanied by rapid development, enhanced by steam power and financial credit.[16] Economic planning at the federal level was deemed necessary by Republican nationalists to promote expansion and encourage private enterprise.[17] At the same time, they tried to "republicanize Hamiltonian bank policy." John C. Calhoun, a representative from South Carolina and strong nationalist, boasted that the nationalists had the support of the yeomanry, who would now "share in the capital of the Bank".[18]

Despite opposition from Old Republicans led by John Randolph of Roanoke, who saw the revival of a national bank as purely Hamiltonian and a threat to state sovereignty,[19] but with strong support from nationalists such as Calhoun and Henry Clay, the recharter bill for the Second Bank of the United States was passed by Congress.[20][21] The charter was signed into law by Madison on April 10, 1816.[22] The Second Bank of the United States was given considerable powers and privileges under its charter. Its headquarters was established in Philadelphia, but it could create branches anywhere. It enjoyed the exclusive right to conduct banking on a national basis. It transferred Treasury funds without charge. The federal government purchased a fifth of the Bank's stock, appointed a fifth of its directors, and deposited its funds in the Bank. B.U.S. notes were receivable for federal bonds.[23]

"Jackson and Reform": Implications for the B.U.S.[edit]

Panic of 1819[edit]

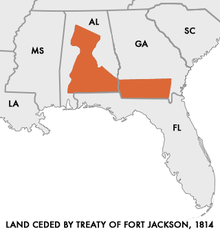

The rise of Jacksonian democracy was achieved through harnessing the widespread social resentments and political unrest persisting since the Panic of 1819 and the Missouri Crisis of 1820.[24] The Panic was caused by the rapid resurgence of the European economy after the Napoleonic Wars, where improved agriculture caused the prices of American goods to drop, and a scarcity of specie due to unrest in the Spanish American colonies. The situation was exacerbated by the B.U.S. under Bank President William Jones through fraud and the rapid emission of paper money. He eventually began to call in loans, but nonetheless was removed by the Bank's directors. Langdon Cheves, who replaced Jones as president, worsened the situation by reducing the Bank's liabilities by more than half, lessening the value of Bank notes, and more than tripling the Bank's specie held in reserve. As a result, the prices of American goods abroad collapsed. This led to the failure of state banks and the collapse of businesses, turning what could have been a brief recession into a prolonged depression. Financial writer William Gouge wrote that "the Bank was saved and the people were ruined".[25]

After the Panic of 1819, popular anger was directed towards the nation's banks, particularly the B.U.S.[24] Many people demanded more limited Jeffersonian government, especially after revelations of fraud within the Bank and its attempts to influence elections.[26] Andrew Jackson, previously a major general in the United States Army and former territorial governor of Florida, sympathized with these concerns, privately blaming the Bank for causing the Panic by contracting credit. In a series of memorandums, he attacked the federal government for widespread abuses and corruption. These included theft, fraud, and bribery, and they occurred regularly at branches of the National Bank.[27] In Mississippi, the Bank did not open branches outside of the city of Natchez, making small farmers in rural areas unable to make use of its capital. Members of the planter class and other economic elites who were well-connected often had an easier time getting loans. According to historian Edward E. Baptist, "A state bank could be an ATM machine for those connected to its directors."[28]

One such example was in Kentucky, where in 1817 the state legislature chartered forty banks, with notes redeemable to the Bank of Kentucky. Inflation soon rose and the Kentucky Bank became in debt to the National Bank. Several states, including Kentucky, fed up with debt owed to the Bank and widespread corruption, laid taxes on the National Bank in order to force it out of existence. In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), the Supreme Court ruled that the Bank was both constitutional and that, as an agent of the federal government, it could not be taxed.[29]

In 1819, Monroe appointed Nicholas Biddle of Philadelphia as Government Director of the Bank. In 1823, he was unanimously elected its president. According to early Jackson biographer James Parton, Biddle "was a man of the pen—quick, graceful, fluent, honorable, generous, but not practically able; not a man for a stormy sea and a lee shore".[30] Biddle believed that the Bank had the right to operate independently from Congress and the Executive, writing that "no officer of the Government, from the President downwards, has the least right, the least authority" to meddle "in the concerns of the Bank".[28]

Rise of Jackson[edit]

The end of the War of 1812 was accompanied by an increase in white male suffrage. Jackson, as a war hero, was popular with the masses. With their support, he ran for president in 1824.[31] The election turned into a five-way contest between Jackson, Calhoun, John Quincy Adams, William H. Crawford, and Clay. All were members of the Republican Party, which was still the only political party in the country.[32] Calhoun eventually dropped out to run for vice president, lowering the number of candidates to four.[33] Jackson won decisive pluralities in both the Electoral College and the popular vote.[34] He did not win an electoral majority, which meant that the election was decided in the House of Representatives, which would choose among the top three vote-getters in the Electoral College. Clay finished fourth. However, he was also Speaker of the House, and he maneuvered the election in favor of Adams, who in turn made Clay Secretary of State, an office that in the past had served as a stepping stone to the presidency. Jackson was enraged by this so-called "corrupt bargain" to subvert the will of the people.[35] As president, Adams pursued an unpopular course by attempting to strengthen the powers of the federal government by undertaking large infrastructure projects and other ventures which were alleged to infringe on state sovereignty and go beyond the proper role of the central government. Division during his administration led to the end of the single party era. Supporters of Adams began calling themselves National Republicans. Supporters of Jackson became known as Jacksonians and, eventually, Democrats.[36]

In 1828, Jackson ran again. Most Old Republicans had supported Crawford in 1824. Alarmed by the centralization in the Adams administration, most of them flocked to Jackson.[37] The transition was made relatively easy by the fact that Jackson's own principles of government, including commitment to reducing the debt and returning power to the states, were largely in line with their own.[38] Jackson ran under the banner of "Jackson and Reform", promising a return to Jeffersonian principles of limited government and an end to the centralizing policies of Adams.[39] The Democrats launched a spirited and sophisticated campaign.[40] They characterized Adams as a purveyor of corruption and fraudulent republicanism, and a menace to American democracy.[41][42] At the heart of the campaign was the conviction that Andrew Jackson had been denied the presidency in 1824 only through a "corrupt bargain"; a Jackson victory promised to rectify this betrayal of the popular will.[43][44]

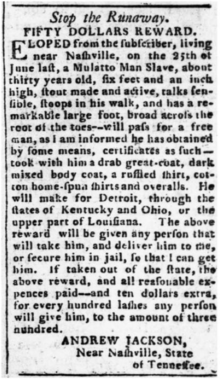

Although slavery was not a major issue in Jackson's rise to the presidency,[38] it did sometimes factor into opposition to the Second Bank, specifically among those in the South who were suspicious of how augmented federal power at the expense of the states might affect the legality of slavery. Democrat Nathaniel Macon remarked, "If Congress can make banks, roads and canals under the Constitution, they can free any slave in the United States."[45] In 1820, John Tyler of Virginia wrote that "if Congress can incorporate a bank, it might emancipate a slave".[46]

Jackson was both the champion and beneficiary of the revival of the Jeffersonian North–South alliance.[47][48][49] The Jacksonian movement reasserted the Old Republican precepts of limited government, strict construction, and state sovereignty.[38] Federal institutions that conferred privileges producing "artificial inequality" would be eliminated through a return to strict constructionism.[50] The "planter of the South and the plain Republican of the North"[51] would provide the support, with the aid of universal white male suffrage.[52] In the end, Jackson won the election decisively, taking 56 percent of the popular vote and 68 percent of the electoral vote.[53]

The Jacksonian coalition had to contend with a fundamental incompatibility between its hard money and paper money factions, for which reason Jackson’s associates never offered a platform on banking and finance reform,[54][55] because to do so "might upset Jackson's delicately balanced coalition".[55] Jackson and other advocates of hard money believed that paper money was part of "a corrupting and demoralizing system that made the rich richer, and the poor poorer". Gold and silver was the only way of having a "fair and stable" currency.[56] The aversion to paper money went back before the American Revolution. Inflation caused during the Revolutionary War by printing enormous amounts of paper money added to the distrust, and opposition to it was a major reason for Hamilton's difficulties in securing the charter of the First Bank of the United States.[57] Supporters of soft money tended to want easy credit.[58] Aspiring entrepreneurs, a number of them on the cotton frontier in the American southwest, resented the Bank not because it printed paper money, but because it did not print more and loan it to them.[59] Banks have to lend more money than they take in. When banks lend money, new money is actually created, which is called "credit". This money has to be paper; otherwise, a bank can only lend as much as it takes in and hence new currency cannot be created out of nothing. Paper money was therefore necessary to grow the economy. Banks making too many loans would print an excess of paper money and deflate the currency. This would lead to lenders demanding that the banks take back their devalued paper in exchange for specie, as well as debtors trying to pay off loans with the same deflated currency, seriously disrupting the economy.[60]

Because of the failure to emphasize the distinction between hard money and paper money, as well as the Bank's popularity, the Second Bank of the United States was not a major issue in the 1828 elections.[61][62] In fact, Biddle voted for Jackson in the election.[63] Jackson himself, though naturally averse to the Bank, had recommended the establishment of a branch in Pensacola. He also signed a certificate with recommendations for president and cashier of the branch in Nashville. The Bank had largely recovered in the public eye since the Panic of 1819 and had grown to be accepted as a fact of life.[64] Its role in managing the nation's fiscal affairs was central. The Bank printed much of the nation's paper money, which made it a target for supporters of hard money, while also restricting the activities of smaller banks, which created some resentment from those who wanted easy credit. As of 1830, the Bank had $50 million in specie in reserve, approximately half the value of its paper currency. It tried to ensure steady growth by forcing state-chartered banks to keep specie reserves. This meant that smaller banks lent less money, but that their notes were more reliable.[65] Jackson would not publicly air his grievances with the B.U.S. until December 1829.[66]

Prelude to war[edit]

Initial attitudes[edit]

When Jackson entered the White House in March 1829, dismantling the Bank was not part of his reform agenda. Although the President harbored an antipathy toward all banks, several members of his initial cabinet advised a cautious approach when it came to the B.U.S. Throughout 1829, Jackson and his close advisor, William Berkeley Lewis, maintained cordial relations with B.U.S. administrators, including Biddle, and Jackson continued to do business with the B.U.S. branch bank in Nashville.[67][68][69]

The Second Bank's reputation in the public eye partially recovered throughout the 1820s as Biddle managed the Bank prudently during a period of economic expansion. Some of the animosity left over from the Panic of 1819 had diminished, though pockets of anti-B.U.S. sentiment persisted in some western and rural locales.[70][71] According to historian Bray Hammond, "Jacksonians had to recognize that the Bank's standing in public esteem was high."[72]

Unfortunately for Biddle, there were rumors that the Bank had interfered politically in the election of 1828 by supporting Adams. B.U.S. branch offices in Louisville, Lexington, Portsmouth, Boston, and New Orleans, according to anti-Bank Jacksonians, had loaned more readily to customers who favored Adams, appointed a disproportionate share of Adams men to the Bank's board of directors, and contributed Bank funds directly to the Adams campaign. Some of these allegations were unproven and even denied by individuals who were loyal to the President, but Jackson continued to receive news of the Bank's political meddling throughout his first term.[73] To defuse a potentially explosive political conflict, some Jacksonians encouraged Biddle to select candidates from both parties to serve as B.U.S. officers, but Biddle insisted that only one's qualifications for the job and knowledge in the affairs of business, rather than partisan considerations, should determine hiring practices.[74] In January 1829, John McLean wrote to Biddle urging him to avoid the appearance of political bias in light of allegations of the Bank interfering on behalf of Adams in Kentucky. Biddle responded that the "great hazard of any system of equal division of parties at a board is that it almost inevitably forces upon you incompetent or inferior persons in order to adjust the numerical balance of directors".[75]

By October 1829, some of Jackson’s closest associates, especially Secretary of State Martin Van Buren, were developing plans for a substitute national bank. These plans may have reflected a desire to transfer financial resources from Philadelphia to New York and other places.[76] Biddle carefully explored his options for persuading Jackson to support recharter.[77] He approached Lewis in November 1829 with a proposal to pay down the national debt. Jackson welcomed the offer and personally promised Biddle he would recommend the plan to Congress in his upcoming annual address, but emphasized that he had doubts as to the Bank's constitutionality. This left open the possibility that he could stymie the renewal of the Bank's charter should he win a second term.[78][79][80]

Annual address to Congress, December 1829[edit]

In his annual address to Congress on December 8, 1829,[81] Jackson praised Biddle's debt retirement plan, but advised Congress to take early action on determining the Bank's constitutionality and added that the institution had "failed in the great end of establishing a uniform and sound currency". He went on to argue that if such an institution was truly necessary for the United States, its charter should be revised to avoid constitutional objections.[66][82] Jackson suggested making it a part of the Treasury Department.[83]

Many historians agree that the claim regarding the Bank’s currency was factually untrue.[66][84][85][86][87] According to historian Robert V. Remini, the Bank exercised "full control of credit and currency facilities of the nation and adding to their strength and soundness".[66] The Bank's currency circulated in all or nearly all parts of the country.[83] Jackson's statements against the Bank were politically potent in that they served to "discharge the aggressions of citizens who felt injured by economic privilege, whether derived from banks or not".[88] Jackson’s criticisms were shared by "anti-bank, hard money agrarians"[89] as well as eastern financial interests, especially in New York City, who resented the national bank's restrictions on easy credit.[90][91] They claimed that by lending money in large amounts to wealthy well-connected speculators, it restricted the possibility for an economic boom that would benefit all classes of citizens.[59] After Jackson made these remarks, the Bank's stock dropped due to the sudden uncertainty over the fate of the institution.[92]

A few weeks after Jackson's address, Biddle began a multi-year, interregional public relations campaign designed to secure a new Bank charter. He helped finance and distribute thousands of copies of pro-B.U.S. articles, essays, pamphlets, philosophical treatises, stockholders' reports, congressional committee reports, and petitions.[93] One of the first orders of business was to work with pro-B.U.S. Jacksonians and National Republicans in Congress to rebut Jackson's claims about the Bank's currency. A March 1830 report authored by Senator Samuel Smith of Maryland served this purpose. This was followed in April by a similar report written by Representative George McDuffie of South Carolina. Smith's report stated that the B.U.S. provided "a currency as safe as silver; more convenient, and more valuable than silver, which ... is eagerly sought in exchange for silver".[94][95] This echoed the arguments of Calhoun during the charter debates in 1816.[96] After the release of these reports, Biddle went to the Bank's board to ask for permission to use some of the Bank's funds for printing and dissemination. The board, which was composed of Biddle and like-minded colleagues, agreed.[97] Another result of the reports was that the Bank's stock rose following the drop that it experienced from Jackson's remarks.[98]

In spite of Jackson's address, no clear policy towards the Bank emerged from the White House. Jackson’s cabinet members were opposed to an overt attack on the Bank. The Treasury Department maintained normal working relations with Biddle, whom Jackson reappointed as a government director of the Bank.[99] Lewis and other administration insiders continued to have encouraging exchanges with Biddle, but in private correspondence with close associates, Jackson repeatedly referred to the institution as being "a hydra of corruption" and "dangerous to our liberties".[100] Developments in 1830 and 1831 temporarily diverted anti-B.U.S. Jacksonians from pursuing their attack on the B.U.S. Two of the most prominent examples were the Nullification Crisis and the Peggy Eaton Affair.[101][102] These struggles led to Vice President Calhoun's estrangement from Jackson and eventual resignation,[102][103] the replacement of all of the original cabinet members but one, as well as the development of an unofficial group of advisors separate from the official cabinet that Jackson's opponents began to call his "Kitchen Cabinet". Jackson's Kitchen Cabinet, led by the Fourth Auditor of the Treasury Amos Kendall and Francis P. Blair, editor of the Washington Globe, the state-sponsored propaganda organ for the Jacksonian movement, helped craft policy, and proved to be more anti-Bank than the official cabinet.[104][105][106]

Annual address to Congress, December 1830[edit]

In his second annual address to Congress on December 7, 1830, the president again publicly stated his constitutional objections to the Bank's existence.[107][108] He called for a substitute national bank that would be wholly public with no private stockholders. It would not engage in lending or land purchasing, retaining only its role in processing customs duties for the Treasury Department.[109][110][111] The address signaled to pro-B.U.S. forces that they would have to step up their campaign efforts.[77][112]

On February 2, 1831, while National Republicans were formulating a recharter strategy, Jacksonian Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri launched an attack against the legitimacy of the Bank on the floor of the Senate, demanding an open debate on the recharter issue. He denounced the Bank as a "moneyed tribunal" and argued for "a hard money policy against a paper money policy".[113][114] After the speech was over, National Republican Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts called for a vote to end discussions on the Bank. It succeeded by a vote of 23 to 20, closer than he would have liked. According to Benton, the vote tally was "enough to excite uneasiness but not enough to pass the resolution".[114] The Globe, which was vigorously anti-B.U.S., published Benton's speech, earning Jackson's praise. Shortly after, the Globe announced that the President intended to stand for reelection.[114][105][106]

Recharter[edit]

Post-Eaton cabinet and compromise efforts[edit]

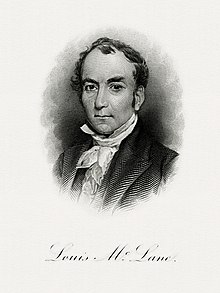

After replacing most of his original cabinet members, Jackson included two Bank-friendly executives in his new official cabinet: Secretary of State Edward Livingston of Louisiana and Secretary of the Treasury Louis McLane of Delaware.[115][116]

McLane, a confidant of Biddle,[117][118] impressed Jackson as a forthright and principled moderate on Bank policy. Jackson called their disagreements an "honest difference of opinion" and appreciated McLane's "frankness".[119] The Treasury Secretary's goal was to ensure that the B.U.S. survived Jackson’s presidency, even in a diminished condition.[120] He secretly worked with Biddle to create a reform package. The product presented to Jackson included provisions through which the federal government would reduce operations and fulfill one of Jackson's goals of paying down the national debt by March 1833. The debt added up to approximately $24 million, and McLane estimated that it could be paid off by applying $8 million through the sale of government stock in the Bank plus an additional $16 million in anticipated revenue. The liquidation of government stock would necessitate substantial changes to the Bank's charter, which Jackson supported. After the liquidation of the debt, future revenues could be applied to funding the military. Another part of McLane's reform package involved selling government lands and distributing the funds to states, a measure consistent with Jackson's overall belief in reducing the operations of the central government. With this accomplished, the administration would permit re-authorization of the national bank in 1836. In return, McLane asked that Jackson not mention the Bank in his annual address to Congress.[121] Jackson enthusiastically accepted McLane's proposal, and McLane personally told Biddle about his success. Biddle stated that he would have preferred that Jackson, rather than remaining silent on the question of recharter, would have made a public statement declaring that recharter was a matter for Congress to decide. Nonetheless, he agreed to the overall plan.[122]

These reforms required a rapprochement between Jackson and Biddle on the matter of recharter, with McLane and Livingston acting as liaisons.[109] The President insisted that no bill arise in Congress for recharter in the lead up to his reelection campaign in 1832, a request to which Biddle assented. Jackson viewed the issue as a political liability—recharter would easily pass both Houses with simple majorities—and as such, would confront him with the dilemma of approving or disapproving the legislation ahead of his reelection. A delay would obviate these risks.[123] Jackson remained unconvinced of the Bank's constitutionality.[124]

Annual address to Congress, December 1831[edit]

Jackson acceded to McLane's pleas for the upcoming annual address to Congress in December, assuming that any efforts to recharter the Bank would not begin until after the election.[125] McLane would then present his proposals for reform and delay of recharter at the annual Treasury Secretary's report to Congress shortly thereafter.[118][126]

Despite McLane's attempts to procure a modified Bank charter,[127] Attorney General Roger B. Taney, the only member of Jackson's cabinet at the time who was vehemently anti-B.U.S., predicted that ultimately Jackson would never relinquish his desire to destroy the national bank.[126][128] Indeed, he was convinced that Jackson had never intended to spare the Bank in the first place.[129] Jackson, without consulting McLane, subsequently edited the language in the final draft after considering Taney’s objections. In his December 6 address, Jackson was non-confrontational, but due to Taney's influence, his message was less definitive in its support for recharter than Biddle would have liked, amounting to merely a reprieve on the Bank’s fate.[125][129][130] The following day, McLane delivered his report to Congress. The report praised the Bank’s performance, including its regulation of state banks,[131] and explicitly called for a post-1832 rechartering of a reconfigured government bank.[125][132]

The enemies of the Bank were shocked and outraged by both speeches.[120][129] The Jacksonian press, disappointed by the president’s subdued and conciliatory tone towards the Bank,[123] launched fresh and provocative assaults on the institution.[133] McLane’s speech, despite its call for radical modifications and delay in recharter,[121] was widely condemned by Jacksonians. They described it as "Hamiltonian" in character, accused it of introducing "radical modifications" to existing Treasury policy and attacked it as an assault on democratic principles. For example, Representative Churchill C. Cambreleng wrote, "The Treasury report is as bad as it can possibly be—a new version of Alexander Hamilton's reports on a National Bank and manufacturers, and totally unsuited to this age of democracy and reform." Secretary of the Senate Walter Lowrie described it as "too ultra federal".[134] The Globe refrained from openly attacking Secretary McLane, but in lieu of this, reprinted hostile essays from anti-Bank periodicals.[125][120][135] After this, McLane secretly tried to have Blair removed from his position as editor of the Globe. Jackson found out about this after Blair offered to resign. He assured Blair that he had no intention of replacing him. Troubled by accusations that he had switched sides, Jackson said, "I had no temporizing policy in me."[135] Although he did not fire McLane, he kept him at a greater distance.[136] Taney's influence meanwhile continued to grow, and he became the only member of the President's official cabinet to be admitted to the inner circle of advisors in the Kitchen Cabinet.[137]

National Republican Party offensive[edit]

National Republicans continued to organize in favor of recharter.[138] Within days of Jackson's address, party members gathered at a convention on December 16, 1831, and nominated Senator Clay for president. Their campaign strategy was to defeat Jackson in 1832 on the Bank re-authorization issue.[133][138][139] To that end, Clay helped introduce recharter bills in both the House and Senate.[140]

Clay and Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster warned Americans that if Jackson won reelection, he would abolish the Bank.[141] They felt secure that the B.U.S. was sufficiently popular among voters that any attack on it by the President would be viewed as an abuse of executive power. The National Republican leadership aligned themselves with the Bank not so much because they were champions of the institution, but more so because it offered what appeared to be the perfect issue on which to defeat Jackson.[133][139]

Administration figures, among them McLane, were wary of issuing ultimatums that would provoke anti-B.U.S. Jacksonians.[77][142] Biddle no longer believed that Jackson would compromise on the Bank question, but some of his correspondents who were in contact with the administration, including McDuffie, convinced the Bank president that Jackson would not veto a recharter bill. McLane and Lewis, however, told Biddle that the chances of recharter would be greater if he waited until after the election of 1832. "If you apply now," McLane wrote Biddle, "you assuredly will fail,—if you wait, you will as certainly succeed."[140] Most historians have argued that Biddle reluctantly supported recharter in early 1832 due to political pressure from Clay and Webster,[139][140][143] though the Bank president was also considering other factors. Thomas Cadwalader, a fellow B.U.S. director and close confidant of Biddle, recommended recharter after counting votes in Congress in December 1831. In addition, Biddle had to consider the wishes of the Bank's major stockholders, who wanted to avoid the uncertainty of waging a recharter fight closer to the expiration of the charter. Indeed, Jackson had predicted in his first annual message of 1829 that the Bank's stockholders would submit an early application to Congress.[144]

On January 6, 1832, bills for Bank recharter were introduced in both houses of Congress.[126][140] In the House of Representatives, McDuffie, as Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, guided the bill to the floor.[145] Fellow Jacksonian George M. Dallas introduced the bill into the Senate.[139] Clay and Webster secretly intended to provoke a veto, which they hoped would damage Jackson and lead to his defeat.[139][146] They did however assure Biddle that Jackson would not veto the bill so close to the 1832 election. The proposals included some limited reforms by placing restrictions on the Bank's powers to own real estate and create new branches, give Congress the ability to prevent the Bank from issuing small notes, and allow the president to appoint one director to each branch of the Bank.[139]

Jacksonian counter-offensive[edit]

The alliance between Biddle and Clay triggered a counter-offensive by anti-B.U.S. forces in Congress and the executive branch.[139][147] Jackson assembled an array of talented and capable men as allies. Most notably, these were Thomas Hart Benton in the Senate and future president James K. Polk, member of the House of Representatives from Tennessee, as well as Blair, Treasury Auditor Kendall, and Attorney General Roger Taney in his cabinets.[148] On February 23, 1832, Jacksonian Representative Augustin Smith Clayton of Georgia introduced a resolution to investigate allegations that the Bank had violated its charter. The intent was to put pro-Bank forces on the defensive.[149][150] These delaying tactics could not be blocked indefinitely since any attempt to obstruct the inquiry would raise suspicions among the public. Many legislators benefited from the largesse supplied by Bank administrators.[126][149][151] The plan was approved, and a bipartisan committee was sent to Philadelphia to look into the matters. Clayton's committee report, once released, helped rally the anti-Bank coalition.[148]

The months of delay in reaching a vote on the recharter measure served ultimately to clarify and intensify the issue for the American people.[152] Jackson’s supporters benefited in sustaining these attacks on the Bank[153] even as Benton and Polk warned Jackson that the struggle was "a losing fight" and that the recharter bill would certainly pass.[152] Biddle, working through an intermediary, Charles Jared Ingersoll, continued to lobby Jackson to support recharter. On February 28, Cambreleng expressed hope that if the recharter bill passed, the President would "send it back to us with his veto—an enduring moment of his fame". The following day, Livingston predicted that if Congress passed a bill that Jackson found acceptable, the President would "sign it without hesitation". In the words of historian Bray Hammond, "This was a very large 'if,' and the secretary came to realize it."[154] Jackson decided that he had to destroy the Bank and veto the recharter bill. Many moderate Democrats, including McLane, were appalled by the perceived arrogance of the pro-Bank forces in pushing through early recharter and supported his decision. Indeed, Livingston was alone in the cabinet, for only he opposed a veto, and Jackson ignored him. Taney's influence grew immensely during this period, and Cambreleng told Van Buren that he was "the only efficient man of sound principles" in Jackson's official cabinet.[155]

Biddle traveled to Washington, D.C. to personally conduct the final push for recharter.[156][157] For the past six months he had worked in concert with B.U.S. branch managers to elicit signatures from citizens for pro-B.U.S. petitions that would be aired in Congress.[158] Congressmen were encouraged to write pro-Bank articles, which Biddle printed and distributed nationally.[159] Francis Blair at the Globe reported these efforts by the B.U.S. president in the legislative process as evidence of the Bank’s corrupting influence on free government.[156] After months of debate and strife, pro-B.U.S. National Republicans in Congress finally prevailed, winning reauthorization of the Bank's charter in the Senate on June 11 by a vote of 28 to 20.[160] The House was dominated by Democrats, who held a 141–72 majority, but it voted in favor of the recharter bill on July 3 by a tally of 107 to 85. Many Northern Democrats joined the anti-Jacksonians in supporting recharter.[161]

The final bill sent to Jackson's desk contained modifications of the Bank's original charter that were intended to assuage many of the President's objections. The Bank would have a new fifteen-year charter; would report to the Treasury Department the names of all of the Bank's foreign stockholders, including the amount of shares they owned; would face stiff penalties if it held onto property for longer than five years, and would not issue notes in denominations of less than twenty dollars. Jacksonians argued that the Bank often cheated small farmers by redeeming paper with discounted specie, meaning that a certain amount was deducted. They alleged that this was unfair to farmers and allowed creditors to profit without creating tangible wealth, while a creditor would argue that he was performing a service and was entitled to profit from it.[162] Biddle joined most observers in predicting that Jackson would veto the bill.[160] Not long after, Jackson became ill. Van Buren arrived in Washington on July 4, and went to see Jackson, who said to him, "The Bank, Mr. Van Buren, is trying to kill me, but I shall kill it."[159][163]

Veto[edit]

Contrary to the assurances Livingston had been rendering Biddle, Jackson determined to veto the recharter bill. The veto message was crafted primarily by members of the Kitchen Cabinet, specifically Taney, Kendall, and Jackson's nephew and aide Andrew Jackson Donelson. McLane denied that he had any part in it.[164] Jackson officially vetoed the legislation on July 10, 1832,[158] delivering a carefully crafted message to Congress and the American people.[165] One of the most "popular and effective documents in American political history",[166] Jackson outlined a major readjustment to the relative powers of the government branches.[167]

The executive branch, Jackson averred, when acting in the interests of the American people,[168] was not bound to defer to the decisions of the Supreme Court, nor to comply with legislation passed by Congress.[169][170] He believed that the Bank was unconstitutional and that the Supreme Court, which had declared it constitutional, did not have the power to do so without the "acquiesence of the people and the states".[171] Further, while previous presidents had used their veto power, they had only done so when objecting to the constitutionality of bills. By vetoing the recharter bill and basing most of his reasoning on the grounds that he was acting in the best interests of the American people, Jackson greatly expanded the power and influence of the president.[172] He characterized the B.U.S. as merely an agent of the executive branch, acting through the Department of the Treasury. As such, declared Jackson, Congress was obligated to consult the chief executive before initiating legislation affecting the Bank. Jackson had claimed, in essence, legislative power as president.[173] Jackson gave no credit to the Bank for stabilizing the country's finances[166] and provided no concrete proposals for a single alternate institution that would regulate currency and prevent over-speculation—the primary purposes of the B.U.S.[166][174][175] The practical implications of the veto were enormous. By expanding the veto, Jackson claimed for the president the right to participate in the legislative process. In the future, Congress would have to consider the president's wishes when deciding on a bill.[172]

The veto message was "a brilliant political manifesto"[176] that called for the end of monied power in the financial sector and a leveling of opportunity under the protection of the executive branch.[177] Jackson perfected his anti-Bank themes. He stated that one fifth of the Bank's stockholders were foreign and that, because states were only allowed to tax stock owned by their own citizens, foreign citizens could more easily accumulate it.[178] He pitted the idealized "plain republican" and the "real people"—virtuous, industrious and free[179][180]—against a powerful financial institution—the "monster" Bank,[181] whose wealth was purportedly derived from privileges bestowed by corrupt political and business elites.[69][182] Jackson's message distinguished between "equality of talents, of education, or of wealth", which could never be achieved, from "artificial distinctions", which he claimed the Bank promoted.[183] Jackson cast himself in populist terms as a defender of original rights, writing:

To those who believed that power and wealth should be linked, the message was unsettling. Daniel Webster charged Jackson with promoting class warfare.[174][185][186] Webster was at around this time annually pocketing a small salary for his "services" in defending the Bank, although it was not uncommon at the time for legislators to accept monetary payment from corporations in exchange for promoting their interests.[187]

In presenting his economic vision,[188] Jackson was compelled to obscure the fundamental incompatibility of the hard-money and easy credit wings of his party.[189] On one side were Old Republican idealists who took a principled stand against all paper credit in favor of metallic money.[190] Jackson's message criticized the Bank as a violation of states' rights, stating that the federal government's "true strength consists in leaving individuals and States as much as possible to themselves."[184] Yet the bulk of Jackson’s supporters came from easy lending regions that welcomed banks and finance, as long as local control prevailed.[191] By diverting both groups in a campaign against the national bank in Philadelphia, Jackson cloaked his own hard-money predilections, which, if adopted, would be as fatal to the inflation favoring Jacksonians as the B.U.S. was purported to be.[192]

Despite some misleading or intentionally vague statements on Jackson's part in his attacks against the Bank, some of his criticisms are considered justifiable by certain historians. It enjoyed enormous political and financial power, and there were no practical limits on what Biddle could do. It used loans and "retainer's fees", such as with Webster, to influence congressmen. It assisted certain candidates for offices over others.[193] It also regularly violated its own charter. Senator George Poindexter of Mississippi received a $10,000 loan from the Bank after supporting recharter. Several months later, he received an additional loan of $8,000 despite the fact that the original loan had not been paid. This process violated the Bank's charter.[194]

Too late, Clay "realized the impasse into which he had maneuvered himself, and made every effort to override the veto".[195] In a speech to the Senate, Webster rebuked Jackson for maintaining that the president could declare a law unconstitutional that had passed Congress and been approved by the Supreme Court. Immediately after Webster spoke, Clay arose and strongly criticized Jackson for his unprecedented expansion, or "perversion", of the veto power. The veto was intended to be used in extreme circumstances, he argued, which was why previous presidents had used it rarely if at all. Jackson, however, routinely used the veto to allow the executive branch to interfere in the legislative process, an idea Clay thought "hardly reconcilable with the genius of representative government". Benton replied by criticizing the Bank for being corrupt and actively working to influence the 1832 election. Clay responded by sarcastically alluding to a brawl that had taken place between Thomas Benton and his brother Jesse against Andrew Jackson in 1813. Benton called the statement an "atrocious calumny". Clay demanded that he retract his statements. Benton refused and instead repeated them. A shouting match ensued in which it appeared the two men might come to blows. Order was eventually restored and both men apologized to the Senate, although not to each other, for their behaviors. The pro-Bank interests failed to muster a supermajority—achieving only a simple majority of 22–19 in the Senate[196]—and on July 13, 1832, the veto was sustained.[197]

The election of 1832[edit]

Jackson's veto immediately made the Bank the main issue of the 1832 election. With four months remaining until the November general election, both parties launched massive political offensives with the Bank at the center of the fight.[198][199] Jacksonians framed the issue as a choice between Jackson and "the People" versus Biddle and "the Aristocracy",[198][200] while muting their criticisms of banking and credit in general.[201] "Hickory Clubs" organized mass rallies, while the pro-Jackson press "virtually wrapped the country in anti-Bank propaganda".[202] This, despite the fact that two-thirds of the major newspapers supported Bank recharter.[203][204]

The National Republican press countered by characterizing the veto message as despotic and Jackson as a tyrant.[205] Presidential hopeful Henry Clay vowed "to veto Jackson" at the polls.[157][206] Overall, the pro-Bank analysis tended to soberly enumerate Jackson's failures, lacking the vigor of the Democratic Party press.[207] Biddle mounted an expensive drive to influence the election, providing Jackson with copious evidence to characterize Biddle as an enemy of republican government and American liberty through meddling in politics. Some of Biddle's aides brought this to his attention, but he chose not to take their advice.[201] He also had tens of thousands of Jackson's veto messages circulated throughout the country, believing that those who read it would concur in his assessment that it was in essence "a manifesto of anarchy" addressed directly to a "mob".[208] "The campaign is over, and I think we have won the victory", Clay said privately on July 21.[209]

Jackson's campaign benefited from superior organization skills. The first ever Democratic Party convention took place in May 1832. It did not officially nominate Jackson for president, but, as Jackson wished, nominated Martin Van Buren for vice president.[210] Jackson's supporters hosted parades and barbecues, and erected hickory poles as a tribute to Jackson, whose nickname was Old Hickory. Jackson typically chose not to attend these events, in keeping with the tradition that candidates not actively campaign for office. Nevertheless, he often found himself swarmed by enthusiastic mobs. The National Republicans, meanwhile, developed popular political cartoons, some of the first to be employed in the nation. One such cartoon was entitled "King Andrew the First". It depicted Jackson in full regal dress, featuring a scepter, ermine robe, and crown. In his left hand he holds a document labelled "Veto" while standing on a tattered copy of the Constitution.[211] Clay was also damaged by the candidacy of William Wirt of the Anti-Masonic Party, which took National Republican votes away in crucial states, mostly in the northeast. In the end, Jackson won a major victory with 54.6% of the popular vote, and 219 of the 286 electoral votes.[212] In Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi, Jackson won with absolutely no opposition. He also won the states of New Hampshire and Maine, fracturing the traditional Federalist/National Republican dominance in New England.[213] The House also stood solidly for Jackson. The 1832 elections provided it with 140 pro-Jackson members compared to 100 anti-Jacksons.[214]

Jackson's dismantling of the B.U.S.[edit]

Renewal of war and 1832 address to Congress[edit]

Jackson regarded his victory as a popular mandate[215] to eliminate the B.U.S. before its 20-year term ended in 1836.[216][217] During the final phase of the 1832 election campaign, Kendall and Blair had convinced Jackson that the transfer of the federal deposits—20% of the Bank's capital—into private banks friendly to the administration would be prudent.[218] Their rationale was that Biddle had used the Bank's resources to support Jackson's political opponents in the 1824 and 1828 elections, and additionally, that Biddle might induce a financial crisis in retaliation for Jackson's veto and reelection.[219] The President declared the Bank "Scotched, not dead".[217][220]

In his December 1832 State of the Union Address, Jackson aired his doubts to Congress whether the B.U.S. was a safe depository for "the people's money" and called for an investigation.[217][220] In response, the Democratic-controlled House conducted an inquiry, submitting a divided committee report (4–3) that declared the deposits perfectly safe.[221] The committee's minority faction, under Jacksonian James K. Polk, issued a scathing dissent, but the House approved the majority findings in March 1833, 109–46.[220] Jackson, incensed at this "cool" dismissal, decided to proceed as advised by his Kitchen Cabinet to remove the B.U.S. funds by executive action alone.[222] The administration was temporarily distracted by the Nullification Crisis, which reached its peak intensity from the fall of 1832 through the winter of 1833.[223] With the crisis over, Jackson could turn his attention back to the Bank.[217]

Search for a Treasury secretary[edit]

Kendall and Taney began to seek cooperative state banks which would receive the government deposits. That year, Kendall went on a "summer tour" in which he found seven institutions friendly to the administration in which it could place government funds. The list grew to 22 by the end of the year.[224] Meanwhile, Jackson sought to prepare his official cabinet for the coming removal of the Bank's deposits.[221][225] Vice President Martin Van Buren tacitly approved the maneuver, but declined to publicly identify himself with the operation, for fear of compromising his anticipated presidential run in 1836.[226][227] Treasury Secretary McLane balked at the removal, saying that tampering with the funds would cause "an economic catastrophe", and reminded Jackson that Congress had declared the deposits secure.[228] Jackson subsequently shifted both pro-Bank cabinet members to other posts: McLane to the Department of State, and Livingston to Europe, as U.S. Minister to France.[229] The President replaced McLane with William J. Duane, a reliable opponent of the Bank from Pennsylvania.[229] Duane was a distinguished lawyer from Philadelphia whose father, also William Duane, had edited the Philadelphia Aurora, a prominent Jeffersonian newspaper. Duane's appointment, aside from continuing the war against the Second Bank, was intended to be a sign of the continuity between Jeffersonian ideals and Jacksonian democracy. "He's a chip of the old block, sir", Jackson said of the younger Duane.[230] McLane met Duane in December 1832 and urged him to accept appointment as Treasury Secretary. He sent a letter of acceptance to Jackson on January 13, 1833, and was sworn in on June 1.[231]

By the time Duane was appointed, Jackson and his Kitchen Cabinet were well-advanced in their plan to remove the deposits.[226][229] Despite their agreement on the Bank issue, Jackson did not seriously consider appointing Taney to the position. He and McLane had disagreed strongly on the issue, and his appointment would have been interpreted as an insult to McLane, who "vigorously opposed" the idea of Taney being appointed as his replacement.[232]

Under the Bank charter terms of 1816, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury was empowered, with Congress, to make all decisions regarding the federal deposits.[233] On his first day at his post, Secretary Duane was informed by Kendall, who was in name his subordinate in the Treasury Department, that Duane would be expected to defer to the President on the matter of the deposits.[222][234][235] Duane demurred, and when Jackson personally intervened to explain his political mandate[215] to ensure the Bank’s demise,[236] his Treasury Secretary informed him that Congress should be consulted to determine the Bank's fate.[237][238] Van Buren had cautiously supported McLane's proposal to delay the matter until January 1, 1834. Jackson declined. To Van Buren, he wrote, "Therefore to prolong the deposits until after the meeting of Congress would be to do the very act [the B.U.S.] wishes, that is, to have it in its power to distress the community, destroy the state Banks, and if possible to corrupt congress and obtain two thirds, to recharter the Bank." Van Buren capitulated.[239]

Jackson's position ignited protest not only from Duane but also McLane and Secretary of War Lewis Cass.[240] After weeks of clashing with Duane over these prerogatives, Jackson decided that the time had come to remove the deposits.[241][242] On September 18, Lewis asked Jackson what he would do in the event that Congress passed a joint resolution to restore the deposits, Jackson replied, "Why, I would veto it." Lewis then asked what he would do if Congress overrode his veto. "Under such circumstances," he said, standing up, "then, sir, I would resign the presidency and return to the Hermitage." The following day, Jackson sent a messenger to learn whether Duane had come to a decision. Duane asked to have until the 21st, but Jackson, wishing to act immediately, sent Andrew Donelson to tell him that this was not good enough, and that he would announce his intention to summarily remove the deposits the next day in Blair's Globe, with or without Duane's consent. Sure enough, the following day, a notice appeared in the Globe stating that the deposits would be removed starting on or before October 1.[243] Secretary Duane had promised to resign if he and Jackson could not come to an agreement. When questioned by Jackson about this earlier promise, he said, "I indescreetly said so, sir; but I am now compelled to take this course." Under attack from the Globe,[244] Duane was dismissed by Jackson days later, on September 22, 1833.[237][241][245] Two days later, McLane and Cass, feeling Jackson had ignored their advice, met with the President and suggested that they resign. They eventually agreed to stay on the condition that they would attend to their own departments and not say anything publicly which would bolster the Bank's standing.[240]

Attorney General Taney was immediately made Secretary of the Treasury[237][246] in order to authorize the transfers, and he designated Kendall as special agent in charge of removal. With the help of Navy Secretary Levi Woodbury, they drafted an order dated September 25 declaring an official switch from national to deposit banking. Beginning on October 1, all future funds would be placed in selected state banks, and the government would draw on its remaining funds in the B.U.S. to cover operating expenses until those funds were exhausted. In case the B.U.S. retaliated, the administration decided to secretly equip a number of the state banks with transfer warrants, allowing money to be moved to them from the B.U.S. These were to be used only to counteract any hostile behavior from the B.U.S.[247]

Removal of the deposits and panic of 1833–34[edit]

Taney, in his capacity as an interim treasury secretary, initiated the removal of the Bank's public deposits, spread out over four quarterly installments. Most of the state banks that were selected to receive the federal funds had political and financial connections with prominent members of the Jacksonian Party. Opponents referred to these banks derisively as "pet banks" since many of them financed pet projects conceived by members of the Jackson administration.[248] Taney attempted to move tactfully in the process of carrying out the removals so as not to provoke retaliation by the B.U.S. or eviscerate the national bank's regulatory influence too suddenly. He presented five state-charted "pet" banks with drafts endorsed by the U.S. Treasury totaling $2.3 million. If Biddle presented any of the state banks with notes and demanded specie as payment, the banks could present him with the drafts to remove the deposits from the Bank and protect their liquidity. However, one of the banks drew prematurely on B.U.S. reserves for speculative ventures.[249] At least two of the deposit banks, according to a Senate report released in July 1834, were caught up in a scandal involving Democratic Party newspaper editors, private conveyance firms, and elite officers in the Post Office Department.[250] Jackson predicted that within a matter of weeks, his policy would make "Mr. Biddle and his Bank as quiet and harmless as a lamb".[251]

Biddle urged the Senate to pass joint resolutions for the restoration of the deposits. He planned to use "external pressure" to compel the House to adopt the resolutions. Clay demurred. Historian Ralph C.H. Catterall writes, "Just as in 1832 Biddle cared 'nothing for the campaign,' so in 1833 Henry Clay cared little or nothing for the bank." Webster and John C. Calhoun, who was now a senator, broke away from Clay. Webster drafted a plan to charter the Bank for 12 years, which received support from Biddle, but Calhoun wanted a 6 year charter, and the men could not come to an agreement.[252]

In the end, Biddle responded to the deposit removal controversy in ways that were both precautionary and vindictive. On October 7, 1833, Biddle held a meeting with the Bank's board members in Philadelphia. There, he announced that the Bank would raise interest rates in the coming months in order to stockpile the Bank's monetary reserves.[253] In addition, Biddle reduced discounts, called in loans, and demanded that state banks honor the liabilities they owed to the B.U.S. At least partially, this was a reasonable response to several factors that threatened the Bank's resources and continued profitability. Jackson's veto and the decreasing likelihood of obtaining a new federal charter meant that the Bank would soon have to wind up its affairs. Then there was the removal of the public deposits, congressional testimony indicating that the Jacksonians had attempted to sabotage the Bank's public image and solvency by manufacturing bank runs at branch offices in Kentucky, the responsibility of maintaining a uniform currency, the administration's goal of retiring the public debt in a short period, bad harvests, and expectations that the Bank would continue to lend to commercial houses and return dividends to stockholders.[254] "This worthy President thinks that because he has scalped Indians and imprisoned Judges, he is to have his way with the Bank. He is mistaken", Biddle declared.[251]

Yet there was also a more punitive motivation behind Biddle's policies. He deliberately instigated a financial crisis to increase the chances of Congress and the President coming together in order to compromise on a new Bank charter, believing that this would convince the public of the Bank's necessity.[255] In a letter to William Appleton on January 27, 1834, Biddle wrote:

At first, Biddle's strategy was successful. As credit tightened across the country, businesses closed and men were thrown out of work. Business leaders began to think that deflation was the inevitable consequence of removing the deposits, and so they flooded Congress with petitions in favor of recharter.[257] By December, one of the President's advisors, James Alexander Hamilton, remarked that business in New York was "really in very great distress, nay even to the point of General Bankruptcy [sic]".[258] Calhoun denounced the removal of funds as an unconstitutional expansion of executive power.[259] He accused Jackson of ignorance on financial matters.[260]

Jackson, however, believed that large majorities of American voters were behind him. They would force Congress to side with him in the event that pro-Bank congressmen attempted to impeach him for removing the deposits. Jackson, like Congress, received petitions begging him to do something to relieve the financial strain. He responded by referring them to Biddle.[261] When a New York delegation visited him to complain about problems being faced by the state's merchants, Jackson responded saying:

The men took Jackson's advice and went to see Biddle, whom they discovered was "out of town".[263] Biddle rejected the idea that the Bank should be "cajoled from its duty by any small driveling about relief to the country."[264] Not long after, it was announced in the Globe that Jackson would receive no more delegations to converse with him about money. Some members of the Democratic Party questioned the wisdom and legality of Jackson's move to terminate the Bank through executive means before its 1836 expiration. But Jackson's strategy eventually paid off as public opinion turned against the Bank.[259][265]

Origins of the Whig Party and censure of President Jackson[edit]

By the spring of 1834, Jackson's political opponents—a loosely-knit coalition of National Republicans, anti-Masons, evangelical reformers, states' rights nullifiers, and some pro-B.U.S. Jacksonians—gathered in Rochester, New York to form a new political party. They called themselves Whigs after the British party of the same name. Just as British Whigs opposed the monarchy, American Whigs decried what they saw as executive tyranny from the president.[266][267] Philip Hone, a New York merchant, may have been the first to apply the term in reference to anti-Jacksonians, and it became more popular after Clay used it in a Senate speech on April 14. "By way of metempsychosis," Blair jeered, "ancient Tories now call themselves Whigs."[266] Jackson and Secretary Taney both exhorted Congress to uphold the removals, pointing to Biddle's deliberate contraction of credit as evidence that the central bank was unfit to store the nation's public deposits.[268]

The response of the Whig-controlled Senate was to try to express disapproval of Jackson by censuring him.[269][270] Henry Clay, spearheading the attack, described Jackson as a "backwoods Caesar" and his administration a "military dictatorship".[271] Jackson retaliated by calling Clay as "reckless and as full of fury as a drunken man in a brothel".[272] On March 28, Jackson was officially censured for violating the U.S. Constitution by a vote of 26–20.[273] The reasons given were both the removal of the deposits and the dismissal of Duane.[274] The opposing parties accused one another of lacking credentials to represent the people. Jacksonian Democrats pointed to the fact that Senators were beholden to the state legislatures that selected them; the Whigs pointing out that the chief executive had been chosen by electors, and not by popular vote.[275]

The House of Representatives, controlled by Jacksonian Democrats, took a different course of action. On April 4, it passed resolutions in favor of the removal of the public deposits.[268][276] Led by Ways and Means Committee chairman James K. Polk, the House declared that the Bank "ought not to be rechartered" and that the deposits "ought not to be restored". It voted to continue allowing the deposit banks to serve as fiscal agents and to investigate whether the Bank had deliberately instigated the panic. Jackson called the passage of these resolutions a "glorious triumph", for it had essentially sealed the Bank's destruction.[277]

When House committee members, as dictated by Congress, arrived in Philadelphia to investigate the Bank, they were treated by the Bank's directors as distinguished guests. The directors soon stated, in writing, that the members must state in writing their purpose for examining the Bank's books before any would be turned over to them. If a violation of charter was alleged, the specific allegation must be stated. The committee members refused, and no books were shown to them. Next, they asked for specific books, but were told that it might take up to 10 months for these to be procured. Finally, they succeeded in getting subpoenas issued for specific books. The directors replied that they could not produce these books because they were not in the Bank's possession. Having failed in their attempt to investigate, the committee members returned to Washington.[278]

In Biddle's view, Jackson had violated the Bank's charter by removing the public deposits, meaning that the institution effectively ceased functioning as a national bank tasked with upholding the public interest and regulating the national economy. Thenceforth, Biddle would only consider the interests of the Bank's private stockholders when he crafted policy.[279] When the committee members reported their findings to the House, they recommended that Biddle and his fellow directors be arrested for "contempt" of Congress, although nothing came of the effort.[280] Nevertheless, this episode caused an even greater decline in public opinion regarding the Bank, with many believing that Biddle had deliberately evaded a congressional mandate.[281]

The Democrats did suffer some setbacks. Polk ran for Speaker of the House to replace Andrew Stevenson, who was nominated to be minister to Great Britain. After southerners discovered his connection to Van Buren, he was defeated by fellow Tennessean John Bell, a Democrat-turned-Whig who opposed Jackson's removal policy. The Whigs, meanwhile, began to point out that several of Jackson's cabinet appointees, despite having acted in their positions for many months, had yet to be formally nominated and confirmed by the Senate. For the Whigs, this was blatantly unconstitutional. The unconfirmed cabinet members, appointed during a congressional recess, consisted of McLane for Secretary of State, Benjamin F. Butler for Attorney General, and Taney for Secretary of the Treasury. McLane and Butler would likely receive confirmation easily, but Taney would definitely be rejected by a hostile Senate. Jackson had to submit all three nominations at once, and so he delayed submitting them until the last week of the Senate session on June 23. As expected, McLane and Butler were confirmed. Taney was rejected by a vote of 28–18. He resigned immediately. To replace Taney, Jackson nominated Woodbury, who, despite the fact that he also supported removal, was confirmed unanimously on June 29. Meanwhile, Biddle wrote to Webster successfully urging the Senate not to support Stevenson as minister.[282]

The Bank's final years[edit]

Demise of the Bank of the United States[edit]

The economy improved significantly in 1834. Biddle received heavy criticism for his contraction policies, including by some of his supporters, and was compelled to relax his curtailments. The Bank's Board of Directors voted unanimously in July to end all curtailments.[283][284][285] The Coinage Act of 1834 passed Congress on June 28, 1834. It had considerable bipartisan support, including from Calhoun and Webster. The purpose of the act was to eliminate the devaluation of gold in order for gold coins to keep pace with market value and not be driven out of circulation. The first Coinage Act was passed in 1792 and established a 15 to 1 ratio for gold to silver coins. Commercial rates tended towards about 15.5-1. Consequentially a $10 gold eagle was really worth $10.66 and 2/3. It was undervalued and thus rarely circulated. The act raised the ratio to 16 to 1. Jackson felt that, with the Bank prostrate, he could safely bring gold back. It was not as successful as Jackson hoped.[286] However, it did have a positive effect on the economy, as did good harvests in Europe. The result was that the recession that began with Biddle's contraction was brought to a close.[283][284] For his part, Jackson expressed his willingness to recharter the Bank or establish a new one, but first insisted that his "experiment" in deposit banking be allowed a fair trial.[287]

Censure was the "last hurrah" of the Pro-Bank defenders and soon a reaction set in. Business leaders in American financial centers became convinced that Biddle's war on Jackson was more destructive than Jackson's war on the Bank.[288][289][290] All recharter efforts were now abandoned as a lost cause.[269] The national economy following the withdrawal of the remaining funds from the Bank was booming and the federal government through duty revenues and sale of public lands was able to pay all bills. On January 1, 1835, Jackson paid off the entire national debt, the only time in U.S. history that has been accomplished.[291] The objective had been reached in part through Jackson's reforms aimed at eliminating the misuse of funds, and through the veto of legislation he deemed extravagant.[292] In December 1835, Polk defeated Bell and was elected Speaker of the House.[293]

On January 30, 1835, what is believed to be the first attempt to kill a sitting President of the United States occurred just outside the United States Capitol. When Jackson was leaving through the East Portico after the funeral of South Carolina Representative Warren R. Davis, Richard Lawrence, an unemployed house painter from England, tried to shoot Jackson with two pistols, both of which misfired.[294] Jackson attacked Lawrence with his cane, and Lawrence was restrained and disarmed.[295] Lawrence offered a variety of explanations for the shooting. He blamed Jackson for the loss of his job. He claimed that with the President dead, "money would be more plenty", (a reference to Jackson's struggle with the Bank) and that he "could not rise until the President fell". Finally, Lawrence told his interrogators that he was a deposed English king—specifically, Richard III, dead since 1485—and that Jackson was his clerk.[296] He was deemed insane and was institutionalized.[297] Jackson initially suspected that a number of his political enemies might have orchestrated the attempt on his life. His suspicions were never proven.[298]

In January 1837, Benton introduced a resolution to expunge Jackson's censure from the Senate record.[299] It began nearly 13 consecutive hours of debate. Finally, a vote was taken, and it was decided 25–19 to expunge the censure. Thereafter, the Secretary of the Senate retrieved the original manuscript journal of the Senate and opened it to March 28, 1834, the day that the censure was applied. He drew black lines through the text recording the censure and beside it wrote: "Expunged by order of the Senate, this 16th day of January, 1837". Jackson proceeded to host a large dinner for the "expungers".[300] Jackson left office on March 4 of that year and was replaced by Van Buren.[301] Including when taking into account the recession engineered by Biddle, the economy expanded at an unprecedented rate of 6.6% per year from 1830 to 1837.[302]

In February 1836, the Bank became a private corporation under Pennsylvania commonwealth law. This took place just weeks before the expiration of the Bank's charter. Biddle had orchestrated the maneuver in a desperate effort to keep the institution alive rather than allowing it to dissolve.[1] This managed to keep the Philadelphia branch operating at a price of nearly $6 million. In trying to keep the Bank alive, Biddle borrowed large sums of money from Europe and attempted to make money off the cotton market. Cotton prices eventually collapsed because of the depression (see below), making this business unprofitable. In 1839, Biddle submitted his resignation as Director of the B.U.S. He was subsequently sued for nearly $25 million and acquitted on charges of criminal conspiracy, but remained heavily involved in lawsuits until the end of his life.[303] The Bank suspended payment in 1839.[304] After an investigation exposed massive fraud in its operations, the Bank officially shut its doors on April 4, 1841.[305]

Speculative boom and Panic of 1837[edit]

Jackson's destruction of the B.U.S. is believed by some to have helped set in motion a series of events that would eventually culminate in a major financial crisis known as the Panic of 1837. The origins of this crisis can be traced to the formation of an economic bubble in the mid-1830s that grew out of fiscal and monetary policies passed during Jackson's second term, combined with developments in international trade that concentrated large quantities of gold and silver in the United States.[306] Among these policies and developments were the passage of the Coinage Act of 1834, actions pursued by Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, and a financial partnership between Biddle and Baring Brothers, a major British merchant banking house.[307] British investment in the stocks and bonds that capitalized American transportation companies, municipal governments, and state governments added to this phenomenon.[308]